Episode 14

[Interview] Natural Systems, Nervous Systems, and Navigating Change | Adam Cooper

Do you know that feeling when you're in a meeting or delivering a speech and you're caught up in thinking about what you want to say next? Then you completely miss the moment when something happens? And you're scrambling to catch up?

This episode hones in on how we can stay more present to what's going on and then respond in the moment to what's happening so we can engage people more effectively and better navigate messy, complex situations.

You’ll learn:

- How diving into the unknown fosters creativity and connection

- Why pre-meeting interactions shape the outcomes of gatherings

- How language influences our identity and decision-making

- Why navigating the unknown requires collective effort and presence

- Four forms of listening that you need to master

- How nature serves as a powerful teacher for leadership.

- How systemic change begins with individual awareness and action.

- Why breath and presence are essential tools for leaders.

- Why savouring the world leads to deeper understanding and connection.

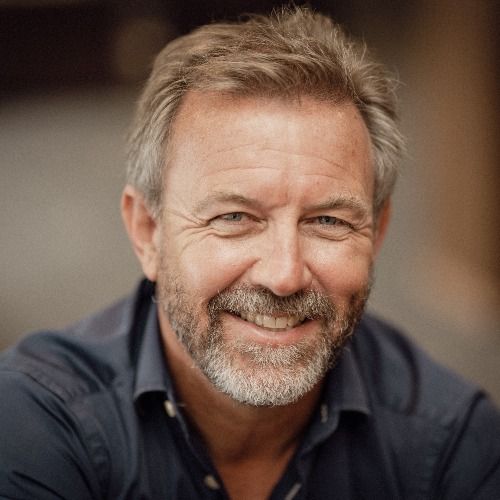

Adam Cooper is one of those people who sees the world just a little bit differently. Adam grew up in Zimbabwe during a time of profound change, watching a society transform before he moved to New Zealand when he was 18. And that experience of seeing how quickly things can shift has shaped his unique lens on leadership and change.

Adam's known for helping leaders and organisations see possibilities they didn't know existed. And he brings a fascinating blend of strategic thinking and embodied wisdom to his work. He's got this uncanny ability to spot patterns and shifts in society long before they become obvious to everyone else.

Adam designs his own path and is a role model for how you can too.

You can find Adam at:

Website: https://www.creativeleadership.co.nz/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/adcoops/

Check out my services and offerings https://www.digbyscott.com/

Subscribe to my newsletter https://www.digbyscott.com/thoughts#subscribe

Follow me on LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/in/digbyscott/

Transcript

and we're rolling. Hey Adam Cooper.

Adam (:Dick Biscott, hello.

Digby (:Nice to see you. You look excited, mate.

Adam (:Yeah, I feel excited. It's good to be here.

Digby (:yeah, you're looking relaxed as ever. And we've just been listening to some blues in the lead up to this. So we're in the groove. Man, you can hear me okay, I take it.

Adam (:Yeah, coming through great.

Digby (:Yeah, and I'm admiring your taste in headphones because I think we have the same taste. It's awesome. I want to start with two words and I'd like you to explain what they mean. So the the two words are Ruku Ao.

What does Ruku Ao mean to you?

Adam (:wow. What a place to begin. my goodness. So lots of layers to this and lots of ways in, but one of them is what's happening in this moment right now, which is that you and I are engaged in a move into the unknown. So I don't speak Te Reo. I'm trying to learn.

Digby (:Ha ha.

Adam (:And I feel really fortunate to live in a country where we are able to learn a different language that is so deeply rooted in the natural world. And so any interpretation I give to those words is going to be very, very limited. It's going to be very, very small and won't at all do justice to the immensity of the stories and the significance that sit behind those words. But as I interpret them,

with my limited understanding through the relationships that I have with people who've told me about those words. One interpretation that's relevant for you and me right now is Ruku is to dive, to enter in. And Ao is the light, so the emerging light or illumination. And so this speaks to this act of diving in or diving towards some kind of

Illumination in sight, light.

Digby (:Now, the reason I wanted to start with that is because if you're listening here, the. Adam texted me probably 20 minutes ago to say, how about we just press record as soon as we go online? And I thought that's diving into the light is diving into the unknown anyway. And so we haven't had any preamble. We.

have just jumped into this conversation. So it's a bit of an experiment and I think it's awesome. think I'm wondering about what this will do for us because I feel like we are both probably still warming up into each other. Right. So which is actually part of the human experience. Yeah. Tell me a little bit more about why this matters, this idea of Ruko Ao to you.

Adam (:Well, I guess, know, sitting here 20 minutes ago or so when I sent that message, was really alive to... There's something that I'm on the edge of exploring, which is when I work with groups and in leadership settings, I'm increasingly seeing the significance of what happens before the thing, you before the meeting, the 10 minutes before the workshop, the lead up, the warm up.

Digby (:Mmm.

Adam (:the interactions that happen prior and how significant they are in shaping what the meeting, what the encounter, what the exchange becomes. so partly my idea or kind of curiosity was to go, what if we made that transparent? And there's all sorts of kind of things I'm curious about in there, like what do you do in the few minutes before you know you're meeting somebody?

or having a podcast or having an encounter. yeah, I was just really curious about that.

Digby (:I love it. It's it's and you know, my response to it was excitement. There was a part of that which is that's not how we do things. That was that bit there. But the majority of it for me when I listened to my response was, hell yeah, let's try that out. Right. And I think there's something in that for all of us is in there. There's just the before the head takes over. Listen to the gut. You know, what's what's what's your body say?

And to me that was like, let's let's be pioneering spirits here. Let's try this out. It's the other thing, by the way, I just want to rewind a little bit for listeners who may not be familiar, particularly outside of New Zealand of Tareo. Tareo is the Maori language. And as an Australian, as an immigrant here, one of things I noticed was. You alluded to it. Coming from a place where.

There are many, many Australian Aboriginal dialects and languages coming here. There's the predominantly the one language with some derivations. How integrated it is relative to where I come from originally into culture here. How do you think that shapes how we think and behave and make choices? What's your experience of that?

Adam (:man, yeah, what a question. So in a way, I'm hearing in your question kind of an inquiry about language, an inquiry about a difference of culture, and an inquiry about how that has shaped me, Yeah, you know, lots of layers. Yeah, lots of layers to dig into there.

Digby (:You

Digby (:Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Digby (:Yeah, all of those.

Yeah, well, choose one, just which is most interesting to you.

Adam (:Well, guess, you know, I guess there's a theme that has flowed through my life and I suspect it'll be relevant for many of your audiences that I come from a family that understands migration and we all do to some extent if we go far enough back. And with migration, inherent in migration is a meeting of worlds, a meeting of places and ideas and in that meeting the potential for

lots of things to happen, know, the potential for friction, potential for pressure, the potential for innovation and life to emerge from that, from that encounter. And so I guess for me, as a person, you know, I'm standing here today, engaging with you, I'm engaging the way that I'm seeing this conversation and you in this moment is shaped by

relationships I have and concepts I have come to understand through certain words in Te Reo Māori. And I think that's significant, not because I want to speak the language so much, but because it takes me deeper into what's true for me in my lineage and in my history. And how can I get a stronger hold on who I am with my Scottish background and my English background and

How can I connect to that in a way that brings me here steadily and in more presence with you in this conversation?

Digby (:And maybe it's an obvious question, but for what purpose? And I'm genuinely curious about that, because this idea of being present in a conversation makes sense. What happens when we're present?

Adam (:Yeah, well, I think we're finding out, right? So I think...

Digby (:Yeah. And even that the kind of the pregnant awkward pause, you know, it's like, hang on, I have to be really present to that question, you know, rather than it being scripted and played out. And we know what's coming next. There's a there's kind of like a rawness, isn't there? There's a there's a dance that you're doing, but it's kind of like a dance that's made up rather than pre scripted steps.

Adam (:100%. There's a immediacy that's called for. There's a depth of listening that's called for and an invitation to kind of listen, not just to what is going on right in front of me, but also what's happening in me and how do I respond to that in a way that's truthful. And so I guess, you know, one way that I'm curious about how we might look at that question about what it enables is it may enable done well.

If we move past the awkwardness and we can tolerate that, maybe it allows or use it. Yeah, yeah. Maybe it allows for something useful to emerge. Maybe it allows for something that previously wasn't known to emerge. And maybe it gets us away from a big tendency in modern Western culture to sort of tell each other what we think and try and convince each other of who's smarter or who's this or that. And actually...

Digby (:Or use it or use it. Yeah.

Digby (:Mm-hmm.

Adam (:be in the unknown together to see what is it that wants to arise between us, whether it's in this conversation or in this meeting or in this work that we're doing for this project or for this time in our organization. So there's maybe more a creative element to it. I suspect there's more of an innovative element to it. And I feel like it's very honoring of us if we can find in ourselves a way to do that because we're genuinely honoring

the potential that exists in the unknown.

Digby (:I love that the potential that exists in the unknown and, know, there's a lot of unknown right now. And just to label or name that there's potential there, not just danger, you know, there's maybe potential for danger, but there's also potential for good and better and exciting and and richness and nourishment and all of those more positive tendencies.

yet we tend to think of unknown often as a. I love, know, it's often the worst case scenario, what's what possibly could go wrong. And I love Reid Hoffman's podcast called Possible because the subtitle is exploring what could possibly go right. And I think we don't look at things often enough with that lens. We tend to look at it as the well, what are we going to lose and.

what's the bad stuff that could happen and how do we mitigate or risk manage around that? And I suspect in your work, because we work in similar fields around leadership development, you might see that propensity. Would that be a fair call? I'm curious about what your experience is.

Adam (:Yeah, yeah, absolutely. We can work out people who do the sort of work that you and I do and leaders in general are calling people into something unknown or trying to build the capacity to respond to the unknown. And in a way, working against a very hardwired neurobiological pattern to crave certainty. It's how we've survived in many respects is to be.

certain and to crave certainty. So whilst we want to honor that, I think, you know, we also want to build in ourselves a capacity to be in the unknown together. And if I'm going to be calling people into that in workshops and coaching, then I need to be able to step into that space myself, keep myself steady, et cetera, et cetera.

Digby (:And we're experiencing it right here. It's interesting, right? We're we're about 10 minutes in and I'm already feeling a shift in how we're talking. It feels like the awkwardness is dialing down and we're getting a bit of flow going on. I'm kind of hesitant to name that because, you know, there's something about popping the bubble there, right? But there's something about noticing that. In fact, you talked about not just listening for what's going on. And I love that. I do a lot of work around.

what I call facilitative leadership and developing that capacity. And I think there's sort of four elements. So I'd love to test these with you for ways of listening. So there's the listening to self. What's going on for you at the time, not just what you're saying, but your state. So noticing awkwardness, for example, in yourself. So that's the first one. There's the relational listening, which is listening to what's going on in the group.

How are people relating to each other? Where are the power dynamics? How are they speaking with each other? Who's speaking the most? Who's tending to lean back or lean forward? So that's that relational thing. That's the second one. So we've got sort of personal and relational. The third one is contextual, which is, so what's the context that's shaping this conversation, this meeting? What's going on around in the wider world?

that might be informing how people are showing up and what they're sharing and what they're not sharing. And the fourth one is directional, is so which direction is this conversation going? What's emerging? How is it aligning with our stated purpose or not? And what stuff that's surprising that's coming out? So personal, relational, contextual and directional. And I think my sense is we tend not to do many of those.

Well, we tend to when we think of listening, we think of what words are they saying or what words am I saying? What comes up as I share that?

Adam (:Hmm. man. Yeah. Well, firstly, I really respect the way that you are kind of digging into different layers, right? And so I think this is a part of what makes your work effective in the sense that you can open up that inquiry from multiple perspectives. So where my mind goes as we explore those layers is

the immediacy of all of those things and how we can be working with them all at once in the same moment. And that's a complex thing. And so as the complexity increases, how do we navigate that? And so to me, it calls into question this idea of how do we navigate in the conversation, in the unknown? And you can extrapolate that to our bigger context as a species. Like, how are we navigating?

Digby (:Yeah.

Digby (:yeah.

Adam (:a massive unknown and can we learn something in conversations that helps build the muscle for us to continue to navigate as a species? Because we always have, we've always adapted, but the conditions now are calling for something a little bit more, you know, perhaps they're a little bit more challenging or they're happening a little bit faster. So I go there and then I also go back to where you started around language. And there's a book that

I found really intriguing, which was called 7,000 Ways to Listen. And the title, you know how a book can just get you at the title? So this was a, and we can leave in the show notes, we can leave the link to it. But what intrigued me about it, obviously beyond the title, was this was an invitation, this book was an invitation to...

Digby (:Ooh, wow. I had four. That's awesome.

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:the idea that there are around 7,000 indigenous languages in the world and that how can we through language start to understand listening. And I'm very excited about that possibility because in my understanding of how language originates, originated from the earth, from nature, from the natural world. So the more we can embed ourselves in that, then

I'm curious about what effect that has around our relationship with each other and with the planet.

Digby (:OK, my brain's spinning here. And if nothing else, perhaps to buy me a little bit of time. I've been thinking it might be useful for people listening to hear a little bit of your context, your your history, your shaping forces. And obviously we could go deep into that. You you grew up, you referred to English and Scottish heritage.

You grew up in Zimbabwe until you were 18. And I'm super curious. And there was it was in the time of quite a powerful societal transition. Can you give us a little bit of a sense of how that shaped the version of Adam that is today? Well, anything the because I think that's an unusual place. It's a rare place.

People live in New Zealand. There's certainly Zimbabweans here, but it's not necessarily a country that a lot of us have an awareness of besides the Magabi more recent era. Tell us a little bit about how that those early years of your life shaped you.

Adam (:Yeah, so a rare and special place to grow up and I think my life has been definitely a privileged one. know, had a fortunate enough to grow up in a loving family. We had access to education and resource and the ability to, I guess, enjoy interaction in and with the natural world in a way that's quite primal. There's something quite incredible about Africa. love speaking to people who've

lived there or traveled there. And the sense they often speak of, of how old the place feels and how it can instill in us this real connection with where we've been in the past, as well as just the natural beauty of the place and so on. And so I think there are elements of having an intimate relationship with the natural world that is possible.

It's possible anywhere in the world, but maybe harder in big cities. So I grew up with, you know, in and around country areas where I was able to get out in the bush and be, you know, beside rivers and on lakes and all of that, which I think is in very large part being something that has shaped me. The other reality about Sub-Saharan Africa and many other countries is that, you know, it's a country

Digby (:Hmm.

Adam (:with a big, rich, somewhat brutal history, colonization, et cetera, has caused all sorts of big, I guess, social and economic challenges. And those still ripple on. And whilst our family had a very privileged time, we weren't immune. Like others who are in Africa might understand this, or if you've spent time there, there's a way in which there's a kind

you can experience things which are quite brutal. And I think when I look back, some of, you know, there was some quite difficult things that my family experienced growing up. They got a little bit caught up in a situation in the civil war in Mozambique when I was quite young. And that was quite a formative experience for me and for my family. And, you know, it's a big, long story perhaps for another day. But what's more important than the details of that hardship is the meaning that

I made from that hardship and one of the things that I really took from that time as a 10 year old with the parents and sister who got caught up in this conflict, I'm deeply and now unknown because I don't know what's going to happen to them. So it's a stressful time and here I am in Zimbabwe living with my relatives and I was very fortunate to be lovingly held and I leant into relationships with people around me.

But I also was able to experience the steadiness, the joy, the peace that can come from being in nature and a very critical moment in my life. And that's something that's carried through my life and it's something that shapes how I work now. So now when I'm working with leaders, I'm increasingly getting them into the outdoors or I'm bringing aspects of the outdoor world into processes around learning and transformation. And that feels very exciting.

Digby (:Can you tell us a little bit about, give us an example of how you do that? Connect the outdoors to the learning for people.

Adam (:Yeah, cool. So an immediate example is last week with a group. I do a lot of work with Outward Bound, which is really rich and rewarding. And for your listeners who know that organization, they might have an experience with that. But I'm down in the Marlborough Sounds last weekend working with a group of leaders. we're working with, in this example, we're working with a particular tree, which is an indigenous tree to New Zealand called the Kahikatea.

And we're able to explore and understand and make visible how that tree grows and how it lives in it when it's strong and when it's weak. So for example, that particular tree grows in a grove where the roots are connected and the extent to which it is connected with others in a living connected ecosystem directly determines its height and strength. And when it grows alone, it tends to be much shorter and weaker.

And as a living ecosystem, it's evolved to communicate. There's science that shows the roots are communicating. They're supporting each other with sending nutrients to trees that are struggling. And so we can explore both through science and through metaphor and through felt experience, we can explore aspects of connection, community, belonging, growth, and then extrapolate that out to, OK, what does this mean for

the way we're resourced, the way we're connected, the way we might grow our connectivity and belonging with other people and where and how might that strengthen us.

Digby (:That's incredibly powerful. The word metaphor you mentioned that came up for me, but also you mentioned science, right? And it's almost like there's, there's this something right there that you cannot ignore, particularly on the metaphor. And I'm imagining the facilitation of the conversation can go really deep with that. What do you notice happens for leaders that you work with in those settings? Typically not necessarily, well, both during the experience and I think

also afterwards, like how do they carry that into an alternative corporate world? What do you see happens?

Adam (:Yeah, so it's interesting because there's a thread of often, you know, often I'm doing multi-day programs or involved in a multi-day process. the first 24 hours is often characterized by them connecting with each other and also disconnecting from the world they've just left, which very often involves leaving their device. So

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:Increasingly, in the last 10 years, I've noticed the impact of being without the device is much more significant. So it's not unusual on day two or three for the group to come into a whole conversation about focus and distraction and the role of tech in our lives and how we can manage that. you know, as an example just recently to be as it's day two on a program, we're down by the beach.

These leaders have been without their devices for maybe just over 24 hours. And this young leader just burst into tears. And she goes, I've just got to tell you. And she's talking to the group here. And she goes, I just got to tell you, I missed having my phone with me. And I was sort of patting my pockets and things. And the longer I'm without it, I feel like I'm coming back to life.

Adam (:So that's thread that flows through and is hard to maintain afterwards, right? It's really hard. And many people leave with a commitment to manage screen time better and commit to being in the outdoors more. And very often they do. And it's hard to sustain in modern Western culture where the forces are on us to hurry, rush, and stay on screens for longer.

Digby (:Yeah, and systemic forces can overcome willpower every time. Right. It's it's that's the thing. Right. You can. I'm hoping, I'm imagining that what last is the idea that may not have been there as clearly before. And at least a commitment that perhaps wasn't there, even though the reality of day to day may not allow that to happen as much as they'd like. I mean, that.

It feels like a bit of a bandaid solution to as I say that, right. It's I'm I'm thinking about systemic change more and more. And, you know, like you, I've I've facilitated a lot of those epiphany experiences, you could call them. And they're incredible. And it's incredibly satisfying when they happen for everyone. And at the same time, that idea of systemic forces being so powerful. What what's your take on?

how we can shift because I think there is a vision of less hurried. Most people really resonate when I talk about unhurried productivity. yeah. Bring that, please. Yet, like you said, the forces are there that get in the way or stop us or push this into a different way of being. What's your take on? What it takes to create that system level change?

Adam (:Yeah, I'm really curious about this and I don't pretend to know the answers, I'm imagining that with any innovation, so one of the things that I'm really interested in is history and looking back, you know, either through the lens of evolutionary biology or history of how tech or innovation has happened, with any innovation, there's a period in which we might, as a species, grapple with it, maybe get burnt by it.

start to understand it and then maybe make more sense of how we might use it with a better understanding of both its potential and its harm. And so in the case of, if you and I talking about screens, I think it feels like I'm optimistic that there'll be a maturing where we will understand more and more about the harm that's caused and be able to manage that. Perhaps much like we might have done with smoking, for example, we might look back on this period and go, you know what, that wasn't healthy.

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:And we found ways to manage that without discarding the whole thing. We found a way to integrate it in a way that's healthy and sustainable. And so I'm really confident that we can do that. And one of the things that gives me that confidence is that I see, you for lot of people, they're not going to have time or resource to spend four days out without their phone. But what I've seen is the impact that can happen when it's just an hour. You know, you might go and sit beside a river.

for half an hour on your lunch break and be able to have a sense of spaciousness and be able to connect with something in you and around you that then can fuel you for the rest of the day. So I think part of what I'm curious about is that we can continue to find ways that are small and accessible and easy to do so that we don't have to take a year in the mountains to kind of recharge, although that's often.

Try this one.

Digby (:Are you saying that system change comes from individual change? And so if we all did that, then we'd have system change.

Adam (:I'm not sure that I'm saying that. think, I think though that that's a really interesting inquiry though, because I noticed that leaders feel a lot of pressure to address systemic issues on their own, which is, which is really hard, right? And it kind of impossible, right? So the forces that we're grappling with, as you say, are systemic. And, and we have access to an individual response, which sometimes feels futile or

insignificant. So I think what I'm saying is that I have hope that life finds a way. And that's what gives me hope that, there are all these systemic things that we can see as maybe dysfunctional, this crisis, this collapse. And those things go hand in hand with regeneration, with new life.

Digby (:Yeah, right.

Digby (:Yes.

Adam (:And I'm very hopeful that as things continue to collapse around us, that life finds a way through and there's possibility and potential everywhere.

Digby (:love that.

I love that life finds a way. It's like Bruce Lee's water will find its way. You know, it's the same idea, isn't it? That also reminds me, I saw a David Attenborough documentary with him reflecting on his 90 odd years on the planet and the changes he's seen it right at the end, he said, you know what, we don't need to save the planet. The planet will be fine. We need to save humanity. And it was quite a stark statement. And

this idea that life will find its way. And ideally, we are life. We're part of life as humans. Right. And so we need to find our way. But we may not be able to control how that happens. You know, there's some bigger forces that we need to go with the flow on. And we have this propensity to think we can control it all. And I think you're you taking people to look at

ecosystems like a forest or a tree in a forest. There's a different lens that can be made possible on how things do change and evolve. Right. There's a there's something incredible there. Yeah, it's. It might feel like a left turn, but I feel like it's also the subset of what we're talking about when you and I first met, which was I think it was about 10 or 11 years ago.

You were in corporate land, as you're not now, right? You're self-employed. And but when I met you, you were a general manager in one of the largest government agencies here in New Zealand. And you made a transition into self-employment a few years later, reflecting back on your time when you were in that kind of corporate structure world that we've just been referring to.

Digby (:What practices served you to stay staying and be on top of it rather than consumed by it?

Adam (:Yeah, yeah. So I guess, you know, I love that question because my early corporate and career life was inside mostly large organizations and in kind of strategy roles. And so it was very, very much centered on performance. And that's kind of, guess, I grew up in the world of this question of how do we perform as humans within organizations and in that context. And I guess

Digby (:Hmm.

Adam (:the more I worked with that and the deeper I went with that, the more important your question became, which is how do I keep myself vital, sustained, hopeful, energetic, purposeful inside of these systems which are well-meaning and also quite flawed in many cases and wonderful and kind of, brutiful.

Digby (:That's a great word. Yeah.

Adam (:in some respects, right? Brutal, know, organizations as we've managed them and designed them and lead them, certainly in the last couple of hundred years, thinking about what we've created and how we've managed to hold on to aspects from organizational life that existed many hundreds of years before.

Digby (:Was that brute-iful? I love it.

Adam (:And when I started to see that, that's what really helped me. So I'll give you an example. If we go back to this idea of what happens before is important. Before you and I kind of grew up inside of these modern organizations, we come from people who were not strangers to organizational life. If we rewind before the big waves of individualism, before the big wave of industrialization,

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:before the big wave of colonization, we knew what communal life meant. We were collaborative, we were agile, we were responsive, we organized and self-organized, we made decisions, we traded, we shared resources. And I don't want to romanticize those times and pretend that they weren't difficult. But there are aspects of what was important in those days and what kept us vital that we see

are still available to us today. And part of that for me to come to your question in a very practical way is that I think there are very practical things we can do centered on the body, centered on maintaining vitality in the body, centered on breathing, centered on nourishing our minds with perspective in a way that we can.

curate the feed of information that we're in to maintain optimism, to maintain a sense of possibility, and so that we can kind of navigate these systems, if we don't do that can kind of, I guess sometimes sweep us off our feet with stress. And you know, I've been in those spaces where it's been pretty stressful.

Digby (:And give us a specific example, if you can remember from back at that time around body breathing. What did you do? What was your routine? What were some of your habits?

Adam (:Well, I guess my pathway into it was through a really difficult experience of having a back injury. So here I am trying to lead a team, trying to get established inside of this organization, and I'm in crippling pain. And I haven't faced in a time like that in my life where I've been in chronic pain for a long time. So it was new, it was difficult. And I think one of the amazing things about it was that it

launched me headlong into an inquiry about breathing. And I remember at the time taking out every book in our local library that I could find about breath, about breathing, and discovering that, you know, it seems absurd when I say this, breathing being such a fundamental human thing, and yet we don't teach our children how to do it, right? We just...

We just let it happen. so I began to experiment and practice with micro pauses, with body scans, with deep breath, and with using the breath as a gateway to awareness. And in really practical ways, it might just be a deep breath while you're in the elevator on your way to the meeting. It might be a quick 30-second body scan head to toe.

while you're sitting waiting for your grumpy stakeholder to arrive. But just finding these ways of coming back to steadiness in the body, coming back to presence. That's what I tried to practice and discover.

Digby (:And what what helped? So what what was the payoff or what what did you notice by deliberately focusing on that? What did that enable?

Adam (:Well, I hope it enabled me to be in some moments perhaps less reactive and more responsive. So I guess this isn't something that I'm here with you today sort of pretending that I've got dialed because I think we move in and out of these spaces, right? But I feel as though when I was able to be inside of a regular practice of regulating my nervous system,

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:It helped me to be clear and it helped me to be calm and it helped me to resist the stress that just comes from being in that environment. And I think if you put that into organizational terms, if we could do that en masse, it equals, and there's lots of science for this, the business case for this I think is well and truly proven, but equals better decisions.

Digby (:this.

Adam (:equals better productivity, equals better health, et cetera, et cetera.

Digby (:It's the slow down to speed up and the breathing is a way of slowing the system. As you said, your nervous system. And I think that just to underscore the react versus respond idea, I think that is so critical and we know that. And if we could just all learn to take a beat or another beat between what happens and then what you do about that, I think that that will

That's a, that's a huge leverage point. And if we could create cultures where that could happen. That would be incredible. It's interesting. I think you model this. My first impression of you, you know, they say, you know, people don't remember what you said or did, but they'll remember how you made them feel my sense of you from back then. You made me feel calm because you were calm and your boss.

was reporting to something like five different ministers and government and all of this. And, know, you were this sort of rock in the storm that to me, you embodied that and being in your presence. I slowed down and I still do, you know, when when we hang out, my mind tends to just slow. And there's something about

I think the way you lead is through modeling. I want, think there's something about, I try to do that as well to, you know, if I'm going to be contributing to system change, one of the roles I can play is to be a model, a role model of choices that I think will certainly sustain me, but also I think can then have a ripple effect on others. And I certainly noticed that in you. just wanted to let you know that because

I think you do know it. And I think you're you're unusual in that way.

Adam (:Thanks, Tukbe. That's really generous. I'm just taking that in. I'm really struck by the notion of the rock. And I can remember vividly a time in Envy where I started to really draw on, in a very real way, the rock.

the metaphor and the imagery around rocks and stones. And in some ways, that's really relevant for what I'm wearing now, which is a piece of jade. And I think I've been lucky to work with and for and alongside a lot of amazing people who have their own practices of this. And what I love about seeing these practices take

they're a more prominent place in the modern workplace, if you think about it as terms in terms of whether it's framed as well-being practice or whatever, is that I feel like it allows for us to work more deliberately with consciousness. And I think that it's that that speaks to your point earlier about that's a way forward for us. You know, I think many of the problems we're seeing in the world are human problems. And so

How can we continue to advance our consciousness and find ways to do that? And of course, the body and our nervous system is one wonderful kind of pathway into that. So that's hopeful for me. And I think it also, in a way, connects with what you were saying about David Attenborough's conversation, because I think the more that I've tried to do that for me personally, the more granular and local my actions have become.

And the more I think and talk, I don't think and talk about saving the world. I think and talk about savoring the world. And that to me feels much more practical and immediate and life-affirming.

Digby (:Yes.

Digby (:Can you just explain a little bit more about what savoring the world means to you?

Adam (:Well, if, and this is hard in modern Western culture, right? So if I can slow down enough to really be in the moment with whoever or whatever I'm with, then, and I can be curious enough to stay with that and savor whatever arises, then I can discover something. And it's through that discovery that I feel I can know who I am more.

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:And if I can know who I am more and more, I can express myself in lots of different ways more and more. And perhaps have more fun and spontaneity and creativity because I'm, I guess, setting aside the preconceived notions of who I was or needed to be or what the world told me I needed to be. And I'm in a process of becoming a dynamic response to the environment that I'm in. And that just feels more fun.

Digby (:The microcosm of that is right now. So I have a big old list of questions that I could be asking. And I've chosen, thanks to your lovely invitation, to just not I have even looked at them. I've been fully present. Well, I think I have trying to be with where this conversation is going, that directional element, right? Like the what's emerging here. And it is about discovery.

Right. You know, big part of this podcast for me is about having me discover something. Listeners discover something and you discover something and we can only do that if we're noticing and being fully present. So that's what you mean by savoring. And I love that. I, I just want to rewind a little to something that stuck in my mind. You said most of our problems are human problems and it reminds me.

Last weekend, I drove my youngest son down to Dunedin, which is towards the bottom of the South Island. It's a university town. He's at university now. I'm an empty nester now. Yay. On the way, we had two days of driving in the car together, which was beautiful. You know, they say if you want to go deep in a conversation, sit in the car with someone, certainly for two days was awesome. He's a profound thinker. He said to me, you know,

All the problems in the world are only problems because we make them problems. I thought, wow, there's so many layers to that. They're only problems because we make them problems. And my mind went to so we can unmake them. And the first thing to do is to be aware of the story we're telling ourselves about what the issue is, and we can only do that by being present to

ourselves and each other about that story rather than you alluded to before this idea of my idea is better than your idea. That's what we should do about it. How do you how do you nudge or facilitate or guide or invite groups to become more present to that way of operating when they're faced with a gnarly pressing issue?

Digby (:that may feel like it's got a lot of time pressure attached to it. How do you bring them to the more present state? What are some of the ways you do that?

Adam (:Yeah, so there's one of the principles I work with is work with what is. And I love your story about sitting with your son as, you know, he's entering this critical transition in life and what a beautiful story in it. And I'm going to speak to your question about how I work with groups through a story that happened with my daughter this week, which you've just sparked. So my youngest daughter hurts her ankle. So she and I find ourselves at the physio.

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:on Monday afternoon and we were in the waiting room before her appointment. And she takes a seat in this, what can be best described as a throne. Like this is a very large, of unreasonably large seat for a waiting room and it's got wooden handle, yeah, arm rests and wooden legs and this kind of very high back. And we start a conversation about the chair and I said to her, I said,

What do you think is the story of this chair? Where did this chair come from? And she, without much thought, she goes, well, I guess the story of this chair begins with the story of the tree that was made into the wood. And then the story of that came from the seed. And the story of that came from another tree and another tree. And so she's doing this naturally, just like your son was very naturally able to.

connect with a deeper truth. And so I think our young people, if the education system hasn't beaten it out of them, which it sounds like from your son and my daughter, maybe it hasn't, that there's this intuitive access that we have to really understanding what, at a deep level, what is behind something and being able to access that from something that's right in front of us. So to come to your question, if I'm working with groups.

work with the principle of what is and will often work with what is right in front of you now. What is the issue, the problem, the emotion, the goal, but to see more deeply into what's behind it, not just what's the symptom, but what is it a symptom of and where did that story start? And let's just unpack and step back and go back and give some context together. And I find that

Digby (:Yeah.

Adam (:When we do that, we can understand much more deeply the systemic forces that are going on. And it suddenly becomes that sense of spaciousness around it becomes, OK, that's what we're inside of. And if we can see that, then maybe we can see a slightly different response.

Digby (:I love it. It's. What seems to be critical there is the the question or questions that you asked to direct attention. So what do you think the origin of this chair is? I think I'm paraphrasing a question, but there's something about where did this come from? You know, that's an unusual question. Yet it invites systemic inquiry, right? There's this, huh?

It I often talk about the idea that the job of creating the new or leadership really, which is the same thing, is this three elements see, imagine and do. And the C is exactly what we talked about. See the see what's actually going on and see the system in the context. Imagine is imagine what could be possible.

or what could be made possible and then do is kind of like do what it takes. But it's it's more nuanced than that is how do you create the conditions to enable that? And I'll often have a sequence of four questions all starting with what. there's the simple first one, which is what or what are we talking about? What's our topic? Then what is which is exactly what you're talking about?

Let's see what is what's actually happening here. What's what all the different angles we can look at this from, including a historical perspective and a systemic perspective. So there's what what is and then there's what if which is now the invitation for possibility in blue sky. And really, what if we could create that or what if we had no constraints or what if we only had a day or whatever it might be? And then the final one is

What next? So what's the directional piece now? What's the next steps, commitments, whatever it is and those middle two, what? What is and what if? I feel like we can often skip over those and go to, well, this is what's happening and this is what we need to do next. And in simple situations, that's really fine, right?

Digby (:But when it comes to messy, complex. Societal shifts, organizational transformation. We need to have the skill and the capacity to go into those bigger sets of questions. I'm hearing we're really aligned on.

Adam (:Yeah.

Adam (:Yeah, I think so. And I'm really aware of the challenges of doing that. And the leaders I'm imagining in your audience are facing huge pressure to not spend much time on those things because there's a pressure towards action. There's a pressure towards progress. There's a pressure towards speed. And that's part of the context. And what it makes difficult is creating the spaciousness, especially collective spaciousness for leadership teams.

Digby (:Hmm.

Digby (:Yes.

Adam (:to be able to make sense of really what's going on. mean, how hard is it to really understand what's going on in the world today? It's not straightforward. So even determining what is, it's a piece of work. And I feel really excited when leaders are prepared to invest in spaciousness for their teams to sit in those middle questions that you named, what is and what's possible.

Digby (:Yes.

Adam (:and to be pliable with the lenses that they apply so they can see something differently. I'm really, one of the quotes I love is by Goethe, the famous German author and scientist, he has a quote that something along the lines of how we see something determines how we treat it and how we treat it determines what it becomes. So the very act of seeing is in itself a transformational act. And can we be more

creative, can we be more pliable, can we look at it through new and different lenses, because if we can do that, we can see something new. And that will allow us to be able to maybe imagine and act in a new way.

Digby (:That's really powerful. Yeah. And it comes back to slow right down. But I also think it's it's not necessarily slow down and do nothing. It's almost like building your toolkit to be in that not rapid space. But, know, again, the slow down to speed up idea, right. It's it's kind of the time you have use it.

use it in a really, really high quality way. And I think what often we do is we kind of, don't know how to be there. So we'll thrash around and then we'll reach for our comfort zone again, because we don't have the tools. And, you know, that includes me, you know, for what I, one of things I'm taking from this conversation is do I really know how to breathe? And I think if I can just be a bit more deliberate about that and make that just part of how I roll.

Then I've got that in my toolkit to use a short amount of time in a very different way to get a very different outcome. And I think it's less about we don't have the time. It's more we don't know how to use the time.

Adam (:Yeah, yeah, great point, great point. That makes me think to be of, you know, this idea of where in the world is performance life and death? And it's in many places, but it's particularly in the military, right? And so if we set aside maybe our moral thoughts about the military or war, and we think about it as the military is one of the most well-resourced

Digby (:Mm-hmm.

Adam (:things that exists in our world in terms of understanding and making an investment in understanding human performance. And if we study what the military has been able to explore in order to have their elite forces, thinking Navy SEALs and so on, really perform under pressure quickly and get a result in a life and death situation, there's a lot of really interesting things in there around the body, around breath, around connection.

and belonging and around really understanding how we can work with consciousness in a group space to enable agility. And if any of your audience are kind of interested in that thread, there's a really good book called Stealing Fire, which gives an insight into what we've learned through modern science and high performance, particularly in a military context, but how that applies in organizations.

Digby (:So we've got a bunch of, we've got a bunch of reading to do. Well, certainly I do after this. I'm conscious that we are getting to a point where we will pause soon. And I'm, curious though, about is there anything that is waiting to be said or explored in your mind that either you'd hope we talk about, or it's just emerged through the conversation.

Adam (:question. It feels like there's something important to pick up on.

Adam (:And I'm noticing, like I'm noticing, I'll often hold this piece of jade that's around my neck. And I think there's something important about how we naturally as humans have ways we can create bridges that take us to a sense of what matters. for me, there's layers and layers of meaning to this piece of stone around my neck and it's a gift and it's

connects to something very, very old. So this is rock that's somewhere between five and 30 million years old. But there's a way in which, even though our workplaces have become maybe more sterile in their natural environment, we still have very natural ways as humans of connecting to the things that remind us of who we are. And so I guess there's something here about

I guess it's a reminder or something that I'm really inspired by is that I see people constantly waking up to what they're doing when it comes to connecting themselves to a bigger story. And they're often doing it without knowing. So there'll be people in your audience who they might've just chosen to wear the earrings that their grandmother gave them on their 21st birthday. Or they might be the cufflinks that you got from dad before he passed away.

But there's this very intuitive way that we have as humans of through adornments and through the way that we decorate our spaces, connecting to something that's bigger. And those things whisper as reminders of who we are. They whisper to us our identity. so I guess there's something there around being able to keep playing with that, keep working with that, keep understanding how that happens for you and

keep feeling the effect of that and how it shows up, reminds you who you are when you're meeting the unknown. So there's something in there and I'm noticing you're pointing behind you, Digby.

Digby (:Yeah. So for folks who can't see this, if you're listening behind me, there's a photograph taken by my brother, who's a photographer is from a drone and it looks down on a piece of coastline. Half of the photo is the ocean and the other half is the Australian landmass. And so you've kind of got this red raw rugged

landmass in this beautiful turquoise ocean. my eldest son on the weekend, we were surfing in Dunedin and he said to me, you're my Poseidon, dad, you know, you're a person who reminds me of where I come from, which is coastal place. And and I was beautiful to hear that. I and I for me,

The reason I think unconsciously until now I've had that photograph on the wall is because a big part of my identity, I'd say I'm a coastal person, not a blue ocean person. I love being in the place between worlds. And I love to be able to navigate uncertainty that happens at that place. I think that's why I love to surf actually, you know, where one force meets another.

That can go quite deep, right? But the idea of having a visual reminder of that right behind me and when I see it every day is exactly what you're talking about. That's why I pointed to it. That's beautiful. Thanks for bringing that up. There's a there's a lot of depth there. As we bring things to a close, one of the questions I love to ask every guest is. What have you learned or discovered through this conversation?

Adam (:I've learned.

The power that exists when we can let go of the way we think something needs to happen and go with the reality of how it is happening and trust ourselves to ride that wave and how that can be scary and fun and feel quite energizing all at the same time.

Digby (:I love it. What a great insight. And finally, how if people want to pick up a conversation with you, how could they find you?

Adam (:So find me on LinkedIn, Adam Cooper on LinkedIn. You can find me and my wife have a website which speaks to some of our work in the world, is creativeleadership.co.nz. So those are the two best places.

Digby (:Brilliant. Adam, absolute legendary conversation. So deep, so resonant as you are. Thanks so much for making the time.

Adam (:It's a pleasure to be, lovely to be with you. See ya.

Digby (:See you soon.