Episode 55

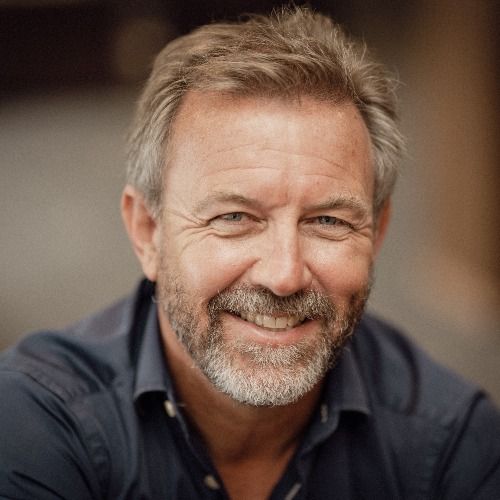

[Interview] Chasing Certainty, Guerrilla Mindfulness, and Teachable Moments | Mike House

What if chasing certainty is actually making you less certain? Most leaders look outward for stability when everything's shifting, but that external focus keeps them perpetually off-balance. When the environment refuses to cooperate with our need for predictability, where do we turn?

This conversation explores a different kind of certainty: the kind that lives inside your team's clarity about who they are, not just what they do. Mike House brings an unexpected lens to leadership development, drawing from 20 years as a survival instructor watching people navigate genuine uncertainty in the outback. He's discovered that the same principles that help someone thrive when stranded with a soapbox-sized survival kit apply when we're leading through complexity.

What's possible when we shift from seeking certainty in circumstances to building it through identity and practice?

Mike spent two decades running what National Geographic called "the toughest thing outside the military anywhere in the world," dropping people into the Australian outback with minimal resources. Now he helps leaders and organisations navigate uncertainty by developing what matters most: the ability to respond rather than react, to spot moments of disproportionate impact, and to create systems that don't need them. He challenges conventional thinking about development, and shows that the most powerful growth often happens in 30-second exchanges we're walking right past.

In this conversation, you'll discover:

• How guerrilla mindfulness, a three-breath practice, can shift your leadership in moments of pressure

• Why looking for certainty in the environment will always leave you more uncertain

• What makes brief mentoring moments more powerful than formal development programmes

• How the gap between circumstance and response is trainable, not fixed

• Why the best mentors might be those creating systems that don't need them

• What survival priorities can teach us about leading through uncertainty

• How to develop the courage to act on teachable moments when you spot them

• Why purpose and identity create more certainty than any strategic plan

Timestamps:

(00:00) - Navigating Uncertainty in Leadership

(17:44) - The Power of Mentoring Moments

(32:12) - Adaptability in Uncertainty

(35:24) - Survival Skills for Business

(39:42) - Creating Conditions for Growth

(43:27) - Identifying Teachable Moments

Other References:

- Pilbara Region

- Box Breathing

- Emotions wheel

- fMRI (Functional Resonance Imaging)

- The Five B’s for Thriving at Work

You can find Mike at:

Website: mikehouse.com.au

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/themikehouse/

Check out my services and offerings https://www.digbyscott.com/

Subscribe to my newsletter https://www.digbyscott.com/subscribe

Follow me on LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/in/digbyscott/

Transcript

If you're looking to the environment for certainty, you're always going to be uncertain. And COVID taught us that in spades, right? Everyone had a plan and then, so, okay, we'll screw that up and make another one and then screw that up because everything just changed and we were doing that almost by the day, globally. But the teams that flourished through that time were really clear about, so who are we as we face this thing?

Digby Scott (:What if the most powerful development moments in your organisation aren't happening in formal mentoring sessions, but instead in those 30 second exchanges you're walking right past?

My guest today, Mike House, spent 20 years as a survival instructor observing people under extreme pressure and he's discovered something really fascinating. The same principles that help people thrive when they're stranded in the outdoors, apply when we're navigating uncertainty or trying to be more adaptable in business. In this conversation, Mike and I explore why looking for certainty in the environment around us will always leave us more uncertain.

and how this idea of guerrilla mindfulness can shift our leadership in three breaths. And why the best mentors might be the ones creating systems that don't need them. If you've ever wondered what it really takes to be adaptive or how to find those moments of disproportionate impact that actually change people, this conversation's for you. Hi, I'm Digby Scott and this is Dig Deeper, a podcast where I have conversations with depth that'll

the way you lead.

Digby Scott (:Welcome to the show.

Thanks Digby, great to be here, thanks for the invite.

wasn't long ago that we're actually sitting together in person in WA at a pub in Lancelin, just north of Perth. And we were saying how much we're both looking forward to actually recording one of these conversations. We've got a similar background is that we're both brought up on farms in the south of Western Australia. Remind us of where you started life.

My folks were farmers down near Nungarin, which is for people familiar with the southwest, sort of a third of the way between Albany and Esperance, a little bit inland and mostly Noongar country down there. And dad came from a long line of Merino stud breeders. you know, big on sheep and wool and all that sort of territory.

Okay. So, and I was brought in just between two towns. was brought up between Bridgetown and Boyup Brook. And it's a little bit closer to Perth. Yeah, we had sheep, had oats, all that sort of stuff. So we've got that farming background and you've had a probably a bit like me, we're a long way from farming, right? You and I, what we do now. And you know, you can never predict your career path in life. You've had a pretty fascinating journey from being raised in that rural environment. You got into

Mike House (:Yeah.

Digby Scott (:I guess, survival instructor training sort of stuff for a long, was about 20 years, I think. And now you're working more into the leadership development space like me. Tell us a bit about that through line, because that's a pretty interesting path to take. What was the sort of the trigger to get into that?

20 years, yeah. Yeah.

Mike House (:A lot like many of your guests, Digby, it's a squiggly line. There was no real plan or forethought really about it. I've always been pretty curious and I reckon growing up on a farm is a great environment to feel that where you get a lot of space and a lot of time to explore if that's kind of in your disposition. know, heaps of curiosity about the world I was inhabiting and

You know, one of the really early experiences down there, I remember sometime in primary school, I decided just in our little one acre farmhouse paddock that I'd try and document all the different kinds of spiders that I could find. And I think I got up to about 75 and went, wow, this is an epically large mission. I was expecting to find about 10. These are different.

types of spiders, not just numbers of spiders.

Yeah, totally different spiders.

So for all the Kiwis or anyone else who's not from Australia listening, freak them out because the myth becomes reality when you hear a story like that.

Mike House (:right? And you know, I had to bat the crocodiles and sharks, so that was a sort of early experience of just being really interested in, what's going on around here. And there's a delightful way that that kind of Bush environment gives you to be able to dip in and out of detail to big picture.

where there's lots to see at the level of what's flowering, what's the seasonal movement look like, all that sort of stuff, and then to really burrow into, what's happening with spiders in this little tiny patch? So that kind of fired up that disposition. And then I took that love of being outside and through my early career did a lot of outdoor education with.

young people at risk and things like that, know, experiential programmes, getting people out of their comfort zone. And I got the opportunity to do a three-day survival course with one of the groups of young people that I was working with. And it was fascinating. I was just really interested in, you know, how do you make a set of circumstances that are really not of your choosing or particularly palatable into something that's

actually fairly relatively easy to manage. So I asked them how I could get involved in that and that was the beginning of that 20 years. I did a course that weekend and then gradually got involved as an instructor and by the end of it I was largely running a 10-day programme that we used to do up in the Pilbara where we'd drop people off with a soapbox sized survival kit and they'd walk around about 200 k's in 10 days looking for food and water on the land.

National Geographic came and filmed it once and said it was the toughest thing they could find outside the military anywhere in the world. pretty epic adventure. Wow.

Digby Scott (:I want to rewind a little bit about what was ignited in you when you came across that survival training stuff, because I also post being a chartered accountant and a few other things got into this outdoor experiential team development stuff as well. And we know a lot of people in common in that industry. I wasn't really that interested in the survival bit. I was interested in what happens to your thinking when you're in nature and you know,

I really want to do something outside for a while, to be honest. But there's something about the survival training thing that I reckon must be different to the average, you know, go and navigate, you know, between A and B and find your way. know, was it about that particular sub industry that was really fascinating for you?

Look for me, it's really about when I and others are under pressure, we can learn a heap about ourselves and there's all sorts of ways to do pressure. You know, I think that's some of the stuff you often talk about with surfing and windsurfing and extreme environments that you've been in. There's that sense of when you're somewhere beyond a known edge, you're

playing in space where there's some sense of competence, but you really don't know what the environment's going to throw at you. You're not entirely sure what the best approach is going to be. And there's some consequence attached. You know, if you get it wrong, there's some genuine risk. Then how do you show up? You know, what does your psyche do? What happens to you physiologically?

And how does all that stuff impact your ability to navigate the territory you're in for, preferably a good outcome. And I think for me, that in itself was just wildly interesting. You know, how comfortable can you make that extremely uncomfortable scenario of being lost or stranded somewhere? And then the secondary bit, which has become the thread into leadership development was, it becomes really obvious in that environment that

Mike House (:line between circumstance and response and how they're loosely coupled where you can have two people, same scenario and one's, that's terrible. So falling off, we're all doomed. the person right next to him is going, this is great. What an adventure. Let's get after it. So I got really fascinated about what sits on that line and how much of that stuff is trainable versus kind of inherently built into a person.

Digby Scott (:What a conclusion there.

So there's definitely personality attributes that, you know, there's all that old, old argument about nature nurture and you definitely see both. You would know from things that you've done that we tend to revert to our most basic type of personality characteristics when the pressure's on, especially if we're underfed, dehydrated, fatigued, and some people do that stuff better than others.

And we can develop it. There's something that happens with exposure to anything that makes it become more familiar where we get better and better at responding and rather than reacting. Yeah, I love that. So that sort of response rather than reaction is a really big piece and we can train that by exposure.

I love that, you know, and which kind of jumped to, well, we're not necessarily out in the bush right now as leaders, but we are facing a lot of unfamiliar territory and, you know, stuff changing a pace. Let's cut to the chase. If there was one practice that anyone could learn to be able to be more responsive, you know, you're in a leadership role at any level. What's that practice?

I'd probably go two levels for that Digby. So at a really personal level, there's a tactic that I call gorilla mindfulness, like gorilla like freedom fighter rather than big black ape, because gorillas are usually out, out gunned and out classed in every way. So they need quick results from something that's, you know, light and easy usually. So gorilla mindfulness, three steps, take three rhythmic breaths.

Mike House (:And the rhythm is important because that's a really powerful physiological signal that we're not in a fight or flight state. It's the only part of that reaction we can control. What about rhythm? Just breathing in and out on a almost like metronome. So, and I talk about rhythm because for you and for me, it might be different.

What is it? Rhythmic breath, what's that?

Mike House (:So, you know, there's lots of versions of it. Some people talk about box breathing where you breathe in for four, pause for four, out for four, pause for four. Yep. It might just be a regular in out, but you're really focusing on the rhythm because the first thing that happens when we start to get overwhelmed is that breathing is one of the first thing that goes. see either people starting to breathe high up in their chest and more rapidly, or they hold their breath.

I get told I forget to breathe and I'm holding my breath for like, you know, I don't know how long it is, but it's like, then suddenly I'm like, Oh, yeah, right. can breathe out. Yeah.

Yeah. And what's curious about that stuff is, you know, if we're even a little bit along the fight or flight continuum, we're measurably more stupid. You can actually put functional, some of us can't afford it. You can put functional resonancing machines on people's brains and actually measure cognitive dysfunction. The whole frontal cortex starts to shut down. And you would have experienced this directly with certainly in surf and

other environments like that where you get barreled and you're just reacting. You're not thinking. And the opposite of that is that kind of flow state, right? Where you're still getting worked, but you're totally calm and you know where the surface is. You're really present. Yeah. Same situation, but really different, really different response. Yeah.

really cool. number one, Breathe.

Mike House (:Number one, breathe and three breaths is enough to kind of get us back to that sense of calm.

You don't need to go on for 10 minutes in a dark room. No, okay.

And it won't necessarily hold, you know, if there's lots of pressure, you might have to keep coming back to that. But three is enough to basically switch that reaction off. Number two is to acknowledge how you feel. And if you can, doing that out loud seems to have a bit of a superpower, but it's not always appropriate facing the corridors of your office going, I feel angry and a bit frustrated.

I often think about you can share your emotion, but you don't have to be emotional. And, know, to be able to have a palette of language, I'll put a link to a thing called the emotions wheel, which is like gives, you know, it's beautiful palette of, you know, probably a hundred different emotions, right? Put that in the show notes. You know, the more literate you are about with the words that you can use to describe how you feel, the more accurate you can be about, okay, this is where I'm at. And.

Yes, correct.

Digby Scott (:be able to name it. agree to be able to have that. I'm feeling despondent. Yeah, rather than sad. This is different. Yeah. And to be able to name that I agree then it's out there and then you can work with it.

And you're really right about the point of this particular exercise is name it, but don't indulge it. So it was really frustrating. You know, I've, I've just come out of a budget meeting. The other people in the business have not kept to their budgets. Our team's been bang on, but we're still being told to tighten our belt. And we know it, you know, we've done everything we can to be in the right spot, but we're still having to do that. So I'll walk out of that frustrated.

I love that.

Mike House (:That frustration is likely not going to be of use to me in whatever I'm doing next. So acknowledging that I'm frustrated, very useful, but carrying that into the next thing I do. Yeah. The next thing I do might be a meeting with a brand new client where we're trying to explore a, you know, a heap of possibilities and ways that we might work together. And if I'm walking into that with frustration, top of mind, I'm not going to be my best self. Yeah. So.

Yeah, good.

Mike House (:Just naming the emotion is a really useful way to kind of give it a place. And it also helps to drop the stress hormones out of our bloodstream. There's a really close link between those two things. And I think it's important to say as well, Digby, especially for us blokes, especially in Australia and probably to a degree New Zealand, this isn't about stuffing emotion down into some dark hole never to be seen again. There are times and places where I'm going to have to deal with that emotion later.

And that could be, you know, take the dog for a walk, spend some time in the bush, phone a friend, have a coffee or a beer or formal therapy or some, you know, deeper work around it. It's not about ignore the emotion. It's just give it its right place. And, you know, this act is mostly about moving through pressure in a moment of pressure. So number one, the rhythmic breaths, number two, how do I feel? And then the third thing.

Which was a, this was built in collaboration with one of my coaching clients, a very busy CEO who said, Mike, that's great in terms of just grounding myself a bit, but it doesn't bloody help with the next thing I'm slamming sideways into. it's like, great point. Great point. Yep. So between us in that conversation, we came up with step three is state your intention for whatever you're going into next.

So if I come out of this frustrated and my next thing's client conversation, then what am I, what do I want out of that conversation? It could be curiosity. could be, you know, clear solutions. It could be building rapport and relationship. You know, let me name that clearly. And then if I'm getting distracted by whatever that stuff behind me or in front of me is, you know, the next meeting or the one before, or something that's going on at home, I can kind of just compartmentalize that.

Mike House (:and stay as close to clear present and focused as I can in this moment.

So let's sum that up. You're facing something unfamiliar, challenging, hard, whatever, scary. Breathe rhythmically, name how you're feeling, and then state your intention for whatever's coming next. Love that. So we spent some good time right now in the last 10 minutes or so, just around kind of like, how do you manage yourself in uncertainty and change and all the hard bits? One area that you're doing more and more work in

is around mentoring. And I think it's a nice shift to like, okay, so this is how we manage ourselves as leaders. Tell us about mentoring. I wanted to ask you because mentoring has been around forever since you know, ancient Greeks and here, you know, and we hear the term mentoring and you know, it's mentoring programmes and you know, I've got a mentor and all. What do people get wrong? When we think about

Yes.

Digby Scott (:mentoring and bringing mentoring into an organisational context. Let's start with that. What do you reckon people get wrong or there's some myths about this thing called mentoring? What do you reckon?

So I think there's a few things there, Digby. One is that we think it's got to take a heap of time. I don't know quite where that comes from. There's perhaps it's just that the standard meeting in a calendar seems to be an hour. So we think it's got to take an hour. Yeah, right. But I'm sure that you've had experiences and I certainly have where somebody, somebody that I admire or trust or has a deep.

wealth of experience or wisdom or knowledge has said something to me or done something with me in a moment of a huge possibility of learning, like it's a real teachable moment. And that's only taken, you know, seconds to minutes, and that's had a lifelong impact. And I can think of several of those, those moments of enormous mentoring impact where somebody's

just sat with me for a little period and just dropped something, an observation, a question, a little bit of guidance or a little bit of correction into a moment. it stuck with me.

So let me test that idea with you with a live example that's coming to mind for me. Cause I'm thinking if I'm listening to this, going, I want to have something to grab hold of. Like what is he, what's talking about here? So I got a voice note from actually rewind a little bit. got an organisation approached me this morning, via email saying, Hey, we'd like you to come and do this piece of work. They gave me a briefing in the email and I looked at it went, I don't think that's me. I don't think that's my thing. was some stuff around helping a team that's a bit dysfunctional.

Digby Scott (:improve. That's not really what I'm about. But I do know someone who is really good at that. And so I sent her a voice note to say, hey, got this opportunity, think might be your space. What do you reckon? And she came back to me with this beautiful articulation of what's needed in a situation like this and how she could help. And this is just to me, I'm not the client. Then here's the point. I know for her that

she's been wanting to position herself and be known as an expert in this space more than she currently is known. I sent her a voice note back saying, hey, I want you to listen back to what you said to me in your voice note and how you articulated it because it was incredible and it makes me very comfortable in referring you because I know that you've got clarity about what you're about and how you help people.

in a way that I've not heard before. That was in my mind, the teachable moment. So was I being a mentor then?

Right. That's a really lovely example, Digby, of, know, there's several features of that. didn't take a huge investment from you. It's not like you had to do a ton of prep. It's not... it was like... Yeah. You jump on, you leave your voice note and mission accomplished. Now, one of the things about this is we're never quite sure about the impact of that. So that could have a massive impact or none. We don't know. But often they're...

Those moments are really profound for somebody. Yes. And I remember one for me, one of the big ones for me, it wasn't even a formal setting. When I was in late high school, I was very uncertain of myself. was in an environment where for lots of reasons, bullying, all sorts of stuff, I was, I was really on the run and I was trying to represent myself as something that I wasn't for standing in a community I really didn't feel I fit into.

Mike House (:And there was this kid much younger than me who stopped me on the steps one day and just said, I'm not really sure who you are. Whoa. And it was this like, whoa, a big moment of, whoa. And it just made me stop and go, no wonder, mate. I don't know. You know, that was a moment of choice then where I've gone, Oh, okay. So if.

like.

Mike House (:That's showing up on the outside. that what I want? Who do I want to be? How do I want to show up? And, and what does that mean for me from here forward? And that kid was probably four or five years younger than me. I couldn't even tell you who he was. I didn't know him well. That's one of those moments that's had a enduring impact on life since, you know, and it was a gift. It was such a gift in that moment.

And in both situations, there was like me letting the person know what or how I was experiencing them in the moment. It was the same for you. So there's something about that as mentoring, which I think maybe we, you know, we often we think as mentoring as I'm going to pass all my wisdom and experience to you. And I think to me, that's a small part of it. How do you define mentoring?

So I think it's any interaction where there's the possibility of a disproportionate impact that has, that's long lasting. Yeah. So any interaction that has the possibility of a disproportional long lasting impact.

Say that again, that's cool.

Digby Scott (:Wow. And we never actually quite know because you could say most interaction have that possibility, right? Yeah.

And it's fascinating because you ask people about this when I run my mentoring programme, one of the things that we do is we just say, okay, so have you, have you got one of those experiences where in less than 15 minutes, something happened that you remember and has coloured everything since then. And almost everybody's got one. And sometimes the person who was the mentor, whether it was an official role or not, knows it.

But often they don't. Whoever they were, they had the courage and or clarity to speak into a moment of time in a way that made a difference.

There you go. There's a lot of coming back to that idea of what's the intention I have. So, you know, when we're leading, we're having conversations all the time. we say that every conversation has that potential to have a disproportionate impact, then probably every conversation has that opportunity in it. You know, it's like, so I need to be intentional at all times.

There was a great example yesterday. I was doing a little bit of work with a bunch of guys who supervised tyre fitters say, you know, they're all hands on tools people. And one of the guys piped up and said, the part of the problem we've got is that we haven't got a clear and shared understanding of what good is and what done is. And I was like, well, mate, there's your opportunity to go mentor some people because the, you know, if you can just speak to some individuals.

Mike House (:and all the whole team together about what good is and what done is and that becomes something shared, your business goes further and faster than it possibly can if those things are fuzzy.

I get this sense that mentoring is almost like, are we trying to formalize this thing too much? This idea of mentoring, you because yeah, you see mentoring programmes. I've been involved in those, you know, I've helped organisations get those going and do all the training and stuff. And I like it as a starting point, but I don't know if it's, I'm just wondering whether are we trying to make mentoring too formal?

That's my sense. So if we look back to your opening question for this chunk Digby about what mistakes do we make, it takes too long and too formal is the other one. So too formal means I'm likely to try and save stuff up for our monthly get together or for the time that's in the calendar. But those mentoring moments where there's lasting impact, they don't happen like that. They more often happen when

You and I are just, you know, we're either on the tools together or we're talking, we're doing some sort of post action review or I've come to you, you know, a lot of the stuff you talk about where someone comes to you for a solution. If you put your hero hat away and put your host hat on and just ask a question or two, then you're being a mentor, I reckon. And in those moments where there's something happening that where it feels.

natural to kind of tease it apart a bit and to explore it in a different way, then that's, you know, the pump's already primed. We're not trying to create something artificial or save it up for a big long session or, you know, God forbid, try and jam it all into an annual performance appraisal or something. Yeah, yeah. So we're noticing those moments and that's the big part of that programme that I run is

Digby Scott (:It'll happen.

Mike House (:getting people switched on to spotting those moments because I think there's some great tools, there's some great frameworks to help people do it well, but if you just show up in the right moment with the right intention, something good's going to happen.

I love the simplicity of that. So let's extrapolate. So say we didn't make mentoring a programme and it was just kind of how we worked, right? What do you reckon the impact of that mindset and that approach would be at scale if mentoring was just built into how we worked? What would happen?

There's again a few layers. So if we go whole organisation kind of layer, it's a really effective way to build both sides of the be and do equation. So if all of us are finding and acting on those moments across the business, over and over over again, we're having conversations about how do we show up? How does this team?

represent itself while we're doing whatever our transactional work is. And, you know, back to these tyre guys yesterday, they've got a massive thing in their business about we, we actually genuinely care. They call it GAF, give a fuck. You know, we genuinely care about our customers and great results and it shows up in spades. You know, they're not just turning up with tyre leavers and rubber. They're like, how can we really work with you? And there's conversations all through that business about what does that actually mean?

That is so cool. I already wanna go there and get my tyres done.

Mike House (:Yeah, yeah, it's awesome. It's a great place to walk into. So at that whole organisation level, those ideas which are often driven by leaders and I think should be the domain of leaders, know, the what direction are we heading strategically in terms of our business, but also culturally, that should be the stuff that leaders care about. And if they don't, it's going to happen by default anyway. So if everybody's mentoring, it helps that stuff.

propagate throughout the organisation and the individual people in it know what it means rather than they're waiting for the boss to show up and go, hey, mate, this way or no, wrong, do it like that, or here's the answer to your problem. So, you you've talked a lot about how do we leave a legacy? It plays a big part in that because you're helping people to see the situation for themselves, to think for themselves.

decide for themselves, solve for themselves.

I think you're on something there, Mike, because I've been thinking about it. What have we shifted this idea of mentoring from a narrow frame? It's about developing people, which it is to something that's more about how do we think about it? Like it's creating systems where we're not needed, you know, where we redundant, like you say, people are thinking for themselves. What if the role of mentoring is about creating those sorts of systems, that sort of culture?

Absolutely. And look, this programme, the High Impact Mentor Programme was actually built out of exactly that problem, did be where I do a lot of work in large not-for-profit organisations in the disability and aged care space. And a lot of the time, their most important staff, the people who provide direct support to people who require it out in the community somewhere, whether that's in their home or out and about.

Mike House (:are working very autonomously and often on their own with one or a small handful of clients. And this organisation, quite a large one, saying, you know, we're just not sure that the frontline mirrors what we wanted to in terms of who we are as an organisation. And there's very few opportunities to actually, you know, see people in action and see what

they're actually up to. And the pressure on formal supervision because of the transactional cadence that we're all under is getting tighter and tighter. you know, in those sectors they used to be at least once a week, everyone would have some sort of formal supervision session with someone up the line from them. And few of them have got the time for that anymore. it's like, yeah, you need opportunities to be

having those discussions without it slowing everything down.

There's something that's coming up for me around it coming back to the survival training stuff around adaptability here. Right. So, you know, for me, you know, yes, mentoring can help people think for themselves more. But I think if it's done really well and not just in a one on one setting, but in a it's becomes part of the how we are as a culture. Surely there's a link to if I'm thinking for myself more, I'm going to learn faster. I'm going to also learn how to learn. So when something new comes up,

Yes.

Digby Scott (:It's not like I've predicted that I know what to do. It's like, actually I know how to adapt. mean, does that make sense?

Yeah, absolutely. So I think the thing with adaptability is people often talk about, you know, trying to forecast or, and when they use that word, they almost mean predict what's going to happen next. And they're trying to build certainty about, you know, we're going to be able to take this step and then that step and then that step. And life is rarely that kind to us. There's loads of information that we don't know.

you know, heaps of gaps, some of that stuff we'll never know. And one of the fascinating things about people is if we have incomplete information, one of the ways we gain certainty is we make stories up to fill the gaps. Yeah, yeah. It's like, don't know, so I'm going to paint the picture.

absolutely.

Digby Scott (:I heard of quote something like 70 % of communication is gossip and gossip is just make making stuff up about people. You know, mean, it's slightly different. I don't know about what's happening with that person, but I'm going to make up a story and that's called gossip. You know, it's that's that's that inaction. Yeah. You think about the doomsday preppers, you know, and the, people that are, you know, what can they teach us about either good or bad about how we be with uncertainty.

So I reckon that there's a really good analog there for forecasting and for preparation for the unknown. And there's some great reality TV and stuff around doomsday preppers if you want to go down that rabbit hole. And there's also some really interesting research and stuff written about it. But essentially people fall onto a continuum where at one extreme there's the person who thinks they know what the apocalypse will look like. They're a hundred percent locked in.

with certainty on zombies or nuclear war or drought or whatever, you know, they've got it all played out in their head and they go build a bunker and they store 10 years worth of whatever to survive the nuclear winter and all of that. And they are so well prepared for that one eventuality that if that comes to pass, they will have the best told you so story in history. Yes.

But the problem with that is if almost anything else happens they are genuinely screwed. If their bunker floods what the hell are going to do then? Their whole plan just got wiped.

So what do you need to develop instead? If it's not a...

Mike House (:So the other end of the extreme is, and this is what we used to teach in the survival school was, you know, what are the priorities we need to look after and how do we make every frame we look through as adaptable as possible. So just one example of that would be, you know, rather than looking at a pair of boots as only a walking tour. So how many things can I do with a bootlace?

And, know, if you start thinking about that, there's a ton of stuff you could do with a bootlace, you know, for an easy and quick thing would be turning into a bow for a fire drill and make yourself a fire, you know, so you've gone from boots to fire. So that way of thinking is what are the high level things I need to look after?

But principles and priorities you're talking about here. Yeah. So what are the big things that matter most and knowing what they are? Yeah.

Yeah. And in survival, there's a really clear five, which are water, warmth, shelter, signals, food, and food almost always is a distant fifth because, you know, unless we haven't eaten for more than 30 days, with the exception of really, really cold climates, there's almost no impact for us. It's horrible. It's not comfortable, but we're not going to die from that. And those priorities float around depending on where you are. So, you know, if we were stuck

down on a glacier in the southern end of your little island in New Zealand there, then warmth and shelter become number one. We've got to get out of the cold, whereas if we're in the desert, shelter number one and water number two, you know, we...

Digby Scott (:Gotcha.

Digby Scott (:Okay. So if we bring it back to, we're not on a glacier, but we're in a, you know, an office building, right? Yeah. So let me test this. So I, I'm thinking about the facilitative leadership that I teach, you know, a bit about that. So it's the leader who's the host, not the hero. And there's something about me and you trained as facilitators. One of the skills that we're, we hone is that you can come into a workshop or a session with a group of people. You can have a plan.

But you need to be able dance on the spot, right? You need to be able to throw that plan out and go, all right, so this is where the energy of the group is. It looks like it's going this way. We need to go that way. And I've learned in my years that I'm good at that. And I've had to hone that agility and adaptability with keeping those principles in mind. I want to test a framework with you that I use when I teach that stuff about what are the conditions that you're trying to

create or pay attention to like the priorities of your life for any group of people to thrive. And I just want to run this past you and for the listeners too. So I think of it like there's, there's four, there's baseline, which is kind of like, do I, am I clear why I'm here? Am I clear? Do I have the tools to do the job? Have I got a place to sit? All that sort of stuff, right? Baseline kind of hygiene factors, then there's belonging, which is

Do I have a sense of connection and a sense that I matter? That if I don't feel like I matter, and we can all think of situations where we felt like the outlier or the reject or whatever. And so I need to feel like I matter as a human. So we've got baseline, then we've got belonging, then it's bringing, which is that I feel like the work matters and I can bring my talents and skills and expertise and perspective

to valuable and important work. If I can't see the why and I can't see a link to what I'm good at, then I'm probably not going to be at my best. And then the final B is becoming, which is that I'm learning, I'm improving every day. So it's baseline belonging, bringing, becoming. Now I'm just thinking about in environments of uncertainty and change and messiness and is my job as a leader, as a mentor or as a

Digby Scott (:someone who's navigating this well other people, is it to just ensure that those conditions are met? And there's a long monologue for me. I just want to test that out loud with you. How does that sit with you?

I love those four Digby. think their depth in that bit of simplicity is delightful. And I reckon yes would be my take on that. I think it's a really cracking example of an equivalence of those survival priorities that could be applied to business. Cause you know, obviously we're not worried about water warm shelter signals, food in your business, unless things have gone really bad.

But we do have me. Yeah, absolutely. And as I'm thinking about those four, if as leaders and mentors, we're creating an environment for people to grow into each of those spaces. And I would add we're clear about what do each of those look like or mean for us as a team? Because, you know, if we're a bunch of people that move in and out of

high risk work sites and we're only there for a short time to do our stuff versus where a group that has, you know, really long advisor type relationships with a group of clients or where, you know, a specific troubleshooting unit or whatever that those things might look quite different. Yeah, yeah. But if we're clear about them, I think that's a great way to build certainty. often say

at the detail level.

Mike House (:that if you're looking to the environment for certainty, you're always going to be uncertain. Yeah. And COVID taught us that in spades, right? Everyone had a plan and then so, okay, we'll screw that up and make another one and then screw that up because everything just changed and we were doing that almost by the day globally. But the teams that flourished through that time.

we're really clear about. So who are we as we face this thing? So they're less worried about what the external is throwing at us. And we're more interested in how do we line up and show up in the face of that. And I reckon those four you've just articulated are a really good frame for doing exactly that. You know, who are we as we face the best and the worst of

the environment that we operate in.

I really like that. It's because that is something that you can have complete control over that story.

Absolutely. It's a hundred percent in-house. No one else gets to have a say in it. And therefore, if you play that well, it's unassailable. It will get tested. It will get tested, but it's largely unassailable because it's down to, regardless of what happens, this is how and who we are. And then in business, we add to that.

Digby Scott (:like that.

Mike House (:You know, what's the transactional stuff that we're here for because we've got to deliver on that. But you know, like you said, with our tyre guys, that's a tyre shop where straight away you go, want my tyres done there. Technically they're no better or worse probably than the 50 others that you could almost throw a stick at from their office. But they've got a really clear sense of, so who are we when we go out to change tyres?

I'm writing down on my notebook here, purpose and identity. So what are we here for and who are we as we bring that to life? That purpose, yeah. Purpose and identity. That's bloody good. Just take a left turn as we start to bring things to a close here. I'm curious about what's the question you're most sitting with at the moment. Like the one that's kind of like you're really digging into for yourself and your work. What are you most curious about at the moment?

So for me, the thing I'm really trying to unpack Digby, and we've done a bit of it in the mentoring programme, but it's still evolving, is how do we find those moments that are very economical in terms of time and resources, but have deep and lasting impact? Yeah, it's my belief that they're everywhere. And I think your example of just those handful of words of encouragement to your friend.

Such a good question.

Mike House (:It's a great example of, you you saw it and you did something with it. And, you know, for you, the cost was almost nil. It didn't take you time, but there wasn't perhaps. So I'm very curious about getting better and better at identifying what those moments look like and preparing myself and others for the courage to use them when you see them.

I love it. I think there's two bits there. One is being able to see them. And then next one is, as you just mentioned, to act on them. Because you can see them and do nothing. Is that actually very helpful? know, it's like, well, what are you going to do with that awareness? And I think it comes back to that. What's my intent here? You know, it's like, am I here to help someone or am I just here to kind of get through the day? You know, it's like, yeah, that's brilliant. How are you going? What are you learning through kind of

holding that question. What are you noticing about how do you find the moments?

So one of the things I'm doing as a bit of a personal practice is I'm looking for them everywhere. And, know, I'm trying to find and therefore am finding, you know, funny how when you look, you find opportunities to practice that in all kinds of environments. So I've had conversations just within the last couple of months with, you know, people who are working on checkouts in supermarkets, people.

pouring my coffee in the morning, people who I'm formally working with at the sort CEO exact kind of level, friends and family where I've been actively looking for moments to do exactly what you did with your friend there and just go, here's an opportunity to drop in a bit of curiosity, a bit of guidance, a bit of correction, a bit of something that gives that person a pause and a possible benefit.

Mike House (:Now what they do with it, that's less in my control. And I deliberately use the word courage Digby because I find that the more I do that, the more audacious I'm getting with the kinds of things I'm noticing and the kinds of things I'll ask or say. And as I do that, the impact is noticeably better. You put yourself out there, it's a bit exposed. You you could, you're never quite sure what's going to come back the other way.

Yeah, too right. So if I'm a leader listening to this conversation and you know, I say, okay, Mike, give me one practical way I can start to identify those moments and then act on them. What would you say I could do?

I think the one that would have the biggest impact both in terms of spotting it and also the impact that it had on the people around you is look for times when a job is well done, either the transactional part of it is well done or how somebody showed up is well done and tell them why as clearly and specifically as you can so that they can repeat that.

And I say that has the biggest impact because, you know, there's all sorts of research about we give greater weight to positive, sorry, negative experiences than positive ones. And most of us in organisations are biased towards the problems we've got to solve, the stuff we've yet to do, rather than the things that we've already done or the things that are going well. And it's a great place to practice, like see how people light up when you notice.

that they're doing a great job and you give them little bit of encouragement and those opportunities are everywhere.

Digby Scott (:Yes, practical wisdom. Yeah, that is so good.

And it's quick, Digby. It's just like you described before where, you know, that could literally be a 30 second interaction. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Now doesn't have to be a meeting. It doesn't have to be formal. It's just, hey, I noticed that fantastic work. Here's why it was fantastic. Do more of that. That's awesome.

There's your script. There's your template. Awesome. Yeah. As we bring things to a close, we've had a bloody great conversation. I've loved this. thing I've learned, I'm going to ask you in a minute, what have you learned? The thing I've learned is this, power of teachable moments is what I'm calling them, right? I think, yeah, I heard it come in my mouth. You've got to identify it and then you've got to act on it. And the way you've said, be courageous about that, that I think gives me permission just to maybe not have it.

perfectly formed, but just to go, I see this thought you might like to know. And yeah, that's really helpful for me. What about for you? What's something that's come up for you? You've learned or been reminded of. That's what we've been talking.

think it's really reminded me of reflecting back on some of those moments, that little example from school, I haven't thought about that for years. So it's reminded me again of the enduring impact that those moments can have and that they don't necessarily have to be in the container of, even in the container of an organisation, you know. For me, this is stuff that

Mike House (:we can all be doing in all sorts of domains of life and it does raise the tide. Yeah, so for me it's that. It's the moments are everywhere. They can sometimes have massive durability and I guess it's just reignited my curiosity to go look for more of them and keep exploring that.

Watch out. man, next time if you know Mike, you're a conversation with him. This is where his radar is going to be.

That's great.

For those of you, or for the people who don't know you and want to find out more about you, how can they find you?

LinkedIn, so I'm on LinkedIn and fairly active there, love to connect with people and have a chat via messages and that sort of thing there. And my website, which is just Mikehouse.com.au are probably the best places.

Digby Scott (:Awesome, mate. And actually, I'm just thinking about the.au. You're in Western Australia. As you know, I'm going to be spending more time there over the coming 12 months.

Exciting.

It's exciting. talking about, you know, needing to be agile and not quite sure how it's going to I'm spending a lot more time planning to come back probably every six weeks for a couple of weeks on average. Anything you could warn me about or tell me what I'm in for as I start to venture into having more time on the ground there and my work and play.

You know, WA is a fascinating place. think because of our isolation, people are fairly innovative and there's a lot of pretty interesting stuff that gets done here that at face value doesn't seem possible. And it's relatively at the moment, I think faster moving than it's ever been. used to be a bit of a quiet backwater and that's no longer true.

There's tons of interesting opportunities, all sorts of pressures. And I think the work you do, Digby, in terms of helping leaders make lasting impact, that stuff is really worthwhile here at the minute because of all the things that we've been talking about where I think there's less and less certainty about what the external environment's going to do. know, here at the moment, everything's massive growth and there's lots of conversations about

Mike House (:various bits of the market are imminently about to tank and some of those conversations have been going on for two years and hasn't happened yet. who knows? The opportunities for leaders to really shape the culture of the organisations they're in, think the time's really right for that kind of work. And there's some fabulous stuff happening here to test some of that stuff out in.

That's great. You know, good to be in a place where there's a lot of energy of change, I reckon. So mate, thanks for that. Nice to know. So yeah, it's a, I'm always up for being in places where there's lots of change. Brilliant, my friend. So awesome. We will, people can find you. put all the links in the show notes to stuff we've talked about and looking forward to seeing you again soon.

Yeah likewise Digby, thanks for the conversation.

It's been awesome. Thanks mate.

Digby Scott (:sitting here after that conversation with Mike, what a practical guy, Just straight shooter, love that. The thing that I'm sitting with is this idea of teachable moments and the ability and courage to see and act on them. And what if we just made that how we worked? You know, we don't do formal mentoring.

So maybe we need to just learn some skills or something. But really then we embed that into just how we have conversations and interact every day. I often talk about this idea that our job as leaders is to help people deliver, make stuff happen, and discover, learn, and grow. And I reckon the teachable moments, it's kind of virtuous, circle. You point one of those out, and that helps them with the discovery, look what I'm capable of. But also then that leads to better delivery.

something to think about. What has this conversation got you thinking? What questions have come up? Go and kick that around. Share this with someone else. If you're interested in growing and developing people, then yeah, that conversation and Mike's expertise is a welfare. Dig into that. I hope that this has been useful. I reckon what else might be useful is if you check out what I write. I'll put in the show notes a link to those four Bs that I talked about.

oing to be there a lot during:Until next time, this is Dig Deeper, I'm Digby Scott, go well.