Episode 32

[Interview] Escaping the ‘Answer Trap’, and Why Slowing Down Speeds You Up

Do you know that feeling when you're asked a question, you’re under pressure, so you reach for the nearest answer?

Or when you're in a meeting and someone says "let's not overcomplicate this" or "we just need to make a decision" and something inside you knows you're moving too fast, but the momentum carries you forward anyway?

This episode explores what Kate Christiansen calls "the Answer Trap," that invisible current pulling us toward quick closure when what we actually need is better thinking.

Kate shares how our brains, when faced with disruption and complexity, default to comfort-seeking patterns that feel like progress but actually limit our capacity to navigate what's really happening.

What if the biggest risk we face isn't making the wrong decision, but stopping our thinking too soon?

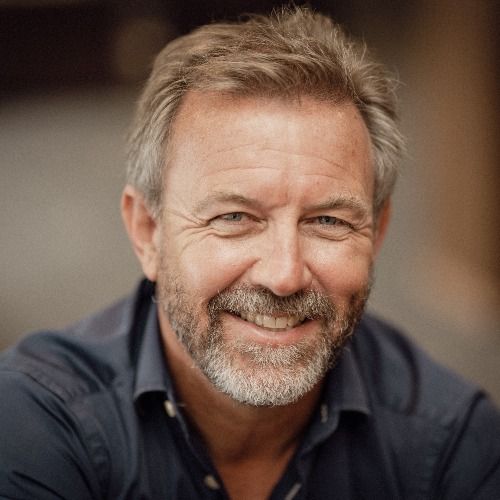

Kate Christiansen is a ‘cognitive detective’ who's spent decades helping leaders think more clearly when it matters most. Having lived through disruptive environments her entire career, she's developed an uncanny ability to see patterns in complexity that others miss.

Kate is the author of "The Answer Trap," a book that names something we've all experienced but never had language for.

In this episode, you'll discover:

- How to recognise the five "autopilot" thinking patterns that drag us toward premature answers

- Why disruption makes us crave closure and how this creates a cycle of reactive decision-making

- How to switch from autopilot to "copilot" by partnering with your brain rather than being controlled by it

- Why asking "What am I thinking right now?" is the simplest way to break free from default patterns

- How AI both amplifies the answer trap and offers new ways to enhance our thinking

- Why the "dodo effect" threatens our cognitive abilities and what we can do about it

- How to create "surface piercing questions" that move beyond comfortable answers

- Why slowing down in conversations actually accelerates better outcomes

Timestamps:

(00:00) - The Dodo Effect and Outsourcing Thinking

(10:57) - The Answer Trap: Understanding the Problem

(20:17) - The Relationship with AI: A Double-Edged Sword

(27:39) - Understanding Autopilots in Decision Making

(32:20) - Breaking Free from Autopilot Thinking

(46:09) - The Power of Naming the Answer Trap

Other references:

- Curly Conversations for Teams Book| Kate Christiansen

- The Answer Trap | Kate Christiansen

- The Thrive Cycle | Kate Christiansen

- Growth Mindset | Carol Dweck

- Chat GPT

You can find Kate at:

Website: www.katechristiansen.com.au

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/katechristiansen/

Check out my services and offerings https://www.digbyscott.com/

Subscribe to my newsletter https://www.digbyscott.com/subscribe

Follow me on LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/in/digbyscott/

Transcript

We’re at a crossroads and wear at risk of what I refer to as the dodo effect. know, dodos weren't dumb. They just moved to an island that didn't have any predators on it. And so they devolved. They reduced the size of their wings. And then when human beings turned up with their domesticated animals, they just wiped the dodo out because they had no longer needed something. And our ability to think,

as humans is what has enabled us to get to where we are now. Now we have a digital brain that we are working with and thinking with. And if we don't work out how we keep our thinking, then what we will do is outsource it to the digital brain.

Digby Scott (:The biggest risk we face isn't making the wrong decision, but stopping our thinking too soon. There's something happening to all of us smart, capable people like us, and we barely notice it. We're reaching for answers faster than ever, especially when the pressure's on. It feels like progress, like we're being decisive, but what if we're actually drifting off course?

Today's guest, Kate Christensen calls this the answer trap. And once you see it, you can't unsee it. She's spent decades as what I'd call a cognitive detective, helping leaders think more clearly when it matters most. This conversation, I think, will change how you meet uncertainty, not with faster answers, but with better questions. I'm Digby Scott, and this is Dig Deeper.

a podcast where I have conversations with depth that will change the way you lead. Let's go.

Digby Scott (:Hey Kate, welcome to the show. Good to be here with you. We live in different cities and we don't spend enough time hanging out. When we first met, there was this immediate connection and I was reflecting earlier on today about that connection, what it was about. And then I pulled out one of your earlier books called Curly Conversations and right in the front of it, you've written, Hey Digby.

So

Digby Scott (:from one curious crusader to another, Kate. And that to me is the essence of our connection, right? We're both deeply curious. I think we come with more questions than answers. I'm curious to start with, where does that come from for you?

I look at the world with, and sometimes I kind of think, is this a naiveness? But actually what I've come to realise over time is I have an absolute wonder as I walk around and wonder about, I wonder where that comes from. And I wonder what they were thinking. And I think it's a feeling, it's a wonderment of not just learning because I want to know things.

like I want to build up this bank of knowledge. It's a learning because I can, because what if there's something underneath? It's that possibility, I think. What about you?

what about me? I've been accused of being kind of like this wonderment freak. think I remember. I remember playing hockey years ago, would have been when I was at university. I remember there must have been a pause in the game for something. Someone was injured or something and we're standing around on the field and a plane flew overhead and I was looking up and going, look at that. There's this metal tube in the sky.

How does that happen? Remember all my teammates just going, eyes on the game DB focus. And I love the way you say it's about the possibility because I think often we focus on the problem and trying to make the problem go away. Yet we're not really focused on the possibility of what else. And I think you're a what else person.

Kate Christiansen (:Yeah, alright!

Kate Christiansen (:Yeah, what else, what's possible, what could be and you know, a bit like you, I suspect this might have been on your report card. I'd like her to spend less time looking out the window and more time focusing on her work.

And that's interesting, right? Because like me, you work with a bunch of different organisations and you know, it's about making stuff happen and delivery and you know, we don't have time for this, do we? I'm curious about that. There I go again. I'm curious about how do you meet with your energy and your wonderment? How do you work with organisations where maybe that feels like a luxury?

think there's a myth that if we slow down, and particularly to do with questions, if we slow down or we ask questions, that they are actually a blocker for us and they will slow us down. And I think in the way that I engage, and I know this is the way that you engage as well, is by being very clear and careful in structured

in the way that I use questions and very careful to make sure that I ask questions, A, that people can answer for now, but is a little bit more of a stretch. And what it does is it moves people forward in a way that doesn't feel like you're just stopping and what people might use, you know, we've got to stop navel gazing. Questions that move you forward are better.

than trying to use answers to move you forward because questions engage the brain and questions get people excited and that's where the possibility lies, right? So I think that's how I do it.

Digby Scott (:I like how you slowed down with your answering, right? You didn't just jump to a perfectly bottled answer. It felt like you were thinking about it as you were talking. The bit that grabbed me there, one of the bits was questions that you can answer for now, but have stretch. And it's interesting that for now bit rather than just the stretch bit, because I think when I'm in hyper questioning mode, I'm probably going way into stretch.

You know, so for example, my partner and I this morning having breakfast and I said, what's the definition of work? We had this fairly philosophical conversation about breakfast. Yeah. Over breakfast. know, this also my curiosity knows no bounds and she's like, I can't easily answer that. Now that stopped her in a tracks. It was a good conversation because she's also super curious. Yeah. At the same time, there's something about the four now, which feels

Like it makes it like we can feel a sense of progress in a good question, right? It's not just about the stretch per se, because progress matters in these environments.

one of the things that, or one of the analogies I often use in terms of using the questions is it's like, if you're going to go to the gym, you need to kind of limber up and stretch and do your stretches before you get onto the equipment. And if we treat the brain as a muscle and that ability to flex between different kinds of thinking that we need for different situations, using

You

Kate Christiansen (:questions as a way to warm up the brain. If you go from cold start to I want all the answers to here's the biggest stretchiest question I could ask you. Often when people are in answer mode, it's very hard for them to switch into that more flexible thinking. And so it's just kind of like limbering up a bit more of a stretch question than another stretch question and keep on stretching them.

until before they know it, the big picture thinking when if I started with that question to start with, that kind of would have been, I don't know the answer.

It bounced straight off them, right? Yeah. The way I think about it is I call them surface piercing questions so we could stay on the surface and bounce along the surface, you know, and that's kind of safe and it's easy. And we probably have to start there, but then we need to dive beneath the surface. Yeah. And kind of what's really going on, you know, and that's a surface piercing question itself, right? Just be able to ask that question. But you don't ask that straight away because all sorts of

bounce straight off, yeah.

Digby Scott (:protective mechanisms can kick in. And so I love the way you say the warm up, but it takes work to remember that. And the tension of we've only got an hour. We've got to get to an end point. We don't have time for warm up. It's interesting as I suspect you see that all the time.

Yeah. And that we don't have time. And interesting in itself is you take one of the things that I talk a lot about is, is orbiting, orbiting and landing and orbiting. Even if you orbit the statement, we don't have time. Okay. Just if we step back from that, what does that mean? Time for what? Who is we? What does we don't have time mean?

And that ability to go most of the time, and I'm sure you find this as well, most of the time, people don't have the same answer for that question. What does we don't have time often actually means I'm feeling uncomfortable in this situation. And what I want to do is that discomfort to end. And we don't have time. I feel uncomfortable. Therefore I want to remove that discomfort.

And anything we'll do, which is where we end up going for the answer that happens to be nearest to us.

And that's a beautiful segue because you've just written this book, The Answer Trap, or in Australian, The Answer Trap.

Kate Christiansen (:You can talk both, can't you?

I'm multilingual. Yeah, it's an incredible book. I remember when you first sent it to me and I read the introduction and it's very rare for me in just reading the introduction to going, this is good. Tell us a little bit about this. Actually, not necessarily about the book. When we talked earlier, you mentioned

that this book feels like a prequel to your other books. And I'm fascinated about that idea. It's like, this is the latest book you've written, but it feels like the first book you could have written. What's going on there? What's that about?

Technically, this is the third book I've written and the first book was an organisational book about how organisations work in systems and adaptiveness. And the second book was about how teams can use questions to connect and collaborate better.

That's a curly conversations book I just shared.

Kate Christiansen (:Kelly Conversations for Teams. so, I mean, this book took a long time to write. And I don't mean it took a long time from beginning to end. I've written about probably six, seven, eight versions of this book. And I've always stopped halfway through. I feel like it's a prequel because I feel like it's got what I've been really trying to say for years in it in terms of connecting the dots for people.

because realizing that, you know, coming from a background where I have, you know, I've kind of lived in disruptive, turbulent environments my entire career. That was what I did. And it was only in recent years, probably the last 10 years, that I realised that the way I was looking at things was different to the way that other people around me saw them.

It seemed like for many people that they didn't know what was happening and they didn't know what was coming. And yet for me, I see patterns in disruption. I see patterns in complexity. And I felt like I couldn't articulate how I knew and what it was. And so really the reason it's the first, well, it feels like it should have been, could have been the first book is that my other books,

make a lot more sense when you see this book, because this is really the why. Why did I write Curly Conversations for Teams? It kind of pulls everything together. It's pulled it out of my head. It had to go deeper than I had to go with anything else, basically.

It sounds like it's an integrating piece. You can produce more stuff in the future and potentially it's going to link back to this. Maybe another way it's a root book, it's the core. It's the thing that you should read first if you want to really make some shifts. Let's talk a little bit about what are we trying to solve here with this book? What is the problem? I suspect we've already been talking about it, but in your words, what's the trigger for this book?

Kate Christiansen (:It's a passion. It's a quest for me as well, because the human brain, what I've noticed and what your listeners and you have noticed is the world is speeding up. Our brain wasn't built for this kind of environment, this kind of disruption. And really many of us take thinking for granted. We take our brains for granted and we just expect it.

to what we want to do. don't think about thinking. What's really happened or is happening is that disruption is speeding up, the world is more complex, our brain can't cope. But what I saw was our brains need help. People don't have a way to connect with their brain because it's inside your head. You can't look at it. It's kind of all this conceptual stuff. And I wanted to make it really concrete for people.

so that they could then partner with and connect with their brain to help it navigate what it needs to deal with and what humanity needs to deal with. So that was on the one side and then on the other, the increasing use of technology, AI particularly, because the book, In Disruption, we want answers and we want them even faster than when we're not disrupted.

Can I ask why that is? Why in disruption do answers have more currency than say questions?

It's because of the impact that disruption has on our brain. So usually we're trying to get things done. So we're trying to make progress is one way that we might describe it. And we're trying to get from where we are to where we want to be, whatever that is. And that's, that's kind of a journey that we're on. When disruption comes along, it puts that path at risk. And the reason that we're pursuing that path.

Kate Christiansen (:is because it meets a need. We want more of something or we want less of something. When disruption comes along, our brain, it triggers that reaction in our brain that says, hang on, something's under threat here. And what it does automatically without us taking a hand in it is it wants to make the discomfort go. That discomfort of not knowing something

It wants that to go and therefore it goes for something that it knows. It goes for an answer that makes us feel like we found clarity. But actually what it's done is it's just created closure. So it's closed off that feeling of discomfort and disruption makes us feel less comfortable. And so you end up in this cycle of comfort seeking behaviour by our brain.

It's the sugar fix, right? It's the I'm hungry, give me some fast food so my hunger goes away, but I don't get nourished by that. That feels like an analogy that fits for me. And I think of my own world and quite simply, you know, when I'm thinking about hosting a podcast conversation like this one, I will want to have some great questions to come prepared with. Right. And the easiest thing to do is to

throw your bio or whatever the book into a GPT or whatever and to say, hey, have a look at this and give me some great questions that I can ask Kate. Now I get that result. There's my sugar fix. I'm set. But am I really set? You am I really ready? And am I really going to bring the best of myself because I don't have to do that work now? Tell us the story. So in the introduction of the book, this is the thing that really hooked me.

into it is the story of how you wrestled with the way you wrote this book.

Kate Christiansen (:As I said, like I tried to write this book multiple times and I just thought I was just sitting at my desk one day and I thought, you know, I use GPT for different things like many of us. And I thought, I'll just put the question to the book. I'd like to write a book on questions. And I can't even remember what the actual question I asked, but whatever it was, it came back.

with the most beautiful, great, this is awesome. Sure, we can do that. What would you like? Do you want the structure? Do you want to have the content? And then I've just gone, gee, that was easy. what if I ask it another question? yeah, well, that first chapter, that sounds great. Let's do the second one. And within, it took me about maybe three days and I had a book and I'm like, how easy is this? And then.

I thought, wow, that'll be awesome. Who wants to write one of these by yourself when you can get ChatGPT to do it? And then I looked at it days later and I thought, hang on. It's smooth. It's articulate. It doesn't have any spelling mistakes, but actually it didn't feel right. It was missing the wrestle that you go through. It was missing the thinking. And coming back to the question around

why write the book is that we are in an era where we have answers on tap. So on the one hand, disruption makes us gravitate to easier answers or the fastest answer. And we switch off our thinking. Once we found the answer, we go, great, done, finished, move on. And now we've also compounding that challenge is that we have

generative AI that we can put something, a question in there and it gives us the answers, not just an average answer, it gives us brilliant answers. And we go, that was awesome. So this is really why I wrote the book because I think, and I say it in the book, we're at a crossroads and we're at risk of what I refer to as the dodo effect. know, dodos weren't dumb.

Kate Christiansen (:They just moved to an island that didn't have any predators on it. And so they devolved. They reduced the size of their wings. And then when human beings turned up with their domesticated animals, they just wiped the dodo out because they had no longer needed something. our ability to think as humans is what has enabled us to get to where we have now. Now we have a digital brain that we are.

working with and thinking with. And if we don't work out how we keep our thinking, then what we will do is outsource it to the digital brain.

brain is atrophying like the dodo's wings right that's the risk. I've got to ask you you know because you and I both publish stuff pretty regularly and all that how do you because AI is not necessarily the villain here right what's your relationship now I am keen to get into the content of the book by the way.

Yeah, that's the risk.

Kate Christiansen (:No.

Kate Christiansen (:No, no, that's fine.

What's your relationship now with something like a chachibe tea? How do you work with it as opposed to say get it to do the work for you? What's the relationship like?

As the top line, I have a love-hate relationship.

That sounds healthy.

Yeah. Yeah. Look, I am absolutely fascinated. So when I'm talking with AI, I do a lot of talking, like just walking around talking with chatGPT. I ask it things like, how did you do that? What were you looking for? Why did you come up with that question? Why did you come up with that answer? Why this? Why that? To understand, because I think we can relate or think that

Kate Christiansen (:chatGPT is thinking and it's not, it's just recognizing patterns. And I like to play a game with it to say, okay, it's just asked me a question and I'll say, what do you think I'm going to say? And pretty much most of the time it's right. So it's got me worked out and my patterns and how I work. And so there's always that little bit of discomfort with that going.

Is that good? Like I hadn't worked out your pattern. You've worked out mine. So it's amazing. It is brilliant. We are lucky to be alive in a time like this. It's very disruptive and it's going to and is challenging many of the foundational things that we just thought were truths. What is intelligence? What is it to be human? What is all these?

Big, big questions. Fascinating.

I love this idea that our superpower is our ability to think and that we can have AI help us to think, but not replace the thinking. Last week, because I'm in the process of pulling together some book ideas and I use Claude rather than ChatGPT, but basically, you know, same, same. And what I found really empowering is asking it to ask me questions.

Yeah. And get me to do the thinking. And I had a whole conversation about this unhurried idea. And I just got it to ask me questions about how I could be thinking about the purpose of this book and the audience I want and questions to get me to really hone my own thinking. And I found that really helpful. And you could say, well, it's replacing my thinking by asking me questions. I found it. It helped me.

Digby Scott (:Develop high quality, not just answers, but perspective. it helped me develop new questions through the process of let's come back to that word, the wrestle. And, I suspect what we're both trying to say here is we need to value the wrestle, you know, value the heart, which is interesting because life is already hard. You know, you're a middle manager in an organisation. Life is not easy. Yeah. Let's come back to the title of the answer trap. So, yeah, say you are a manager and you're

listening to this and you're leading a team. How do you fall into the answer trap? I'll give us an example of what that might look like.

The first thing is a situation. So a situation, you might have a plan. You might have a plan. You're trying to get something done. And as I was talking about before, you know, we're all trying to make progress. You'll be trying to make progress in something. And generally other people want you to make progress in that thing as well, which is how it all works and projects, cetera. And what will happen is something goes off or so there's this feeling that something isn't right.

And often the best way to see the answer trap is actually not to see it. It's actually to listen for it. So you can listen around other people and what they're saying. So some of the things they might say is, look, let's not overcomplicate this. Is a great signal that maybe there's not.

necessarily a tolerance or a willingness to go into the detail or to this thing that is complex. We want to keep it really simple. So listening out for that sort of phrase, things have gone off track. If someone says, look, we've just got to stick to the plan. None of these are bad phrases. Like they're useful. Sometimes you do need to stick to the plan. The thing about the answer trap is that it is invisible. In the book, I talk about it.

Kate Christiansen (:use the analogy of it's like a rip current and on the surface, it looks like everything's going really well. It looks like you are thinking well because you're making decisions, you're moving forward, you're ticking things off the box. But actually, if you look underneath, what you find is that there is this default thinking. It's a thinking habit that just goes, well, okay, I want something quickly.

The reason we don't want things complicated is because they make us uncomfortable. And what we need is a way to sit in that discomfort because that's where the best thinking comes from. sometimes, you know, might be things like, I don't have time for this, which is what we talked about before. I just need to make a decision. If you hear someone say, I just need to make a call or I just need to make a decision.

That is a prime scenario where you can feel, you can feel the energy dragging you to an answer.

I was in a workshop yesterday with a leadership team and one of them in there, absolutely that on steroids and was not comfortable holding the tension and being in the gray. It sounds like one of the archetypes of autopilots, which is language you use in the book, right? It sounds like that's if I'm right, is that the driver?

There's five autopilots and they are patterns of thinking that we default to. One of those patterns is the driver pattern. some different people default to different ones. And in the book, you get to work out which one is yours and, which one you default to. The driver wants to make progress and wants momentum and will push those things forward. But we all have our own versions of

Kate Christiansen (:What are the things that drag us in? And this was, we were talking before about the book, why I wrote it why I think it's the prequel to my other books is that because we can't see what's going on in our head, we assume when we're being reactive, because really this is another way of saying we're going from reactive thinking when we want, we want is some kind of response, something more thoughtful. One of the things that we do is we assume that reactive thinking looks the same for everybody.

And what I explain with the autopilots is depending on which autopilot kicks in during your time of discomfort, that will create the lens through which you are looking at whatever this situation, this disruption that you've experienced is.

Let's make that real. What's your one that you tend to default to out of those five? Which is the predominant one for you?

So I have two that are relatively strong. One is the connector. The connector autopilot is this pattern is to connect people, ideas to keep the system whole. And when things come up, disruption happens. Someone who defaults to connector like me will be there going, where is everybody on this? Who's on first? What do they think? What do they believe is the case? Etc. The other one that

to that one.

Kate Christiansen (:is very strong for me is pioneer. So I'm a connector pioneer way of thinking. So pioneer being, you know, let's explore possibility. There must be another different way we could do this, all that sort of thing. And the key thing with the autopilots is that they are a default. It's not that it's bad thinking because actually that thinking works really well sometimes, but it's that we default to that and apply a thinking that may not be useful.

in this situation.

I want to ask you what you think mine might be, because you know me reasonably well. What do you reckon? And maybe for the listeners, shall we just run through them that there's the driver, which you've mentioned.

There's the driver, there is the fact finder. The fact finder searches for information to find as much information as possible. There's the pioneer that I mentioned, looks for discovery and exploration. The connector, which I talked about earlier. And then there's the optimiser. The optimiser is the polisher, the refiner, the thinking pattern that looks to take what you've got and perfect it.

Okay, what am I?

Kate Christiansen (:What are you? I think you are probably pioneer.

with a smidgen of...

Digby Scott (:Yeah, you're right. I reckon I'm pioneer. I'm always going, is this the right question to be asking? You know, that sort of thing that is often helpful, but sometimes really annoying because it doesn't. The drivers don't like that. Right. Yes. Definitely a connector. Like, where is everyone in this? I think that's right. That would be secondary for me. And thirdly, I would say it's probably the fact finder. I won't drive for closure fast. What else do we need to know? And so

You can see that they're all in us, right? There's, you know, I've just listed off three or five and and I like the way that they're not wrong. They're just more of a default way of being. If I'm not aware of these things, or maybe even I am and say I spot that I'm doing that, what's my way out of the trap? Like, what's the first step that I can take when I'm noticing I'm in autopilot mode? What do I do?

One of the really cool things about the answer trap and getting out of it, because if you notice that you are operating on autopilot, i.e. your natural or your, feels natural thinking is not best for this situation. So that's the scenario by simply noticing that you might be operating on autopilot. have just switched off autopilot. Do you see? Because.

Ha.

The simplest thing that you can say, and I know you ask these questions, is to ask yourself, what am I thinking right now? Now, when you first do it, my clients tell me, usually what they get back is, I don't know what I'm thinking. Because when you're not used to asking yourself and talking to your brain, talking to yourself, I highly recommend it. It's one of the least

Kate Christiansen (:rated things, but it is talking to yourself because what you learn is you start to hear the voice that comes back. That response of, don't know what I'm thinking. okay. Great. Well, what might I be thinking? So all you're trying to do with the answer trap, the answer trap is everywhere and we all fall into it and we fall into it in teams. We fall into it individually. We fall as society. It's everywhere. The good news is that you can

easily break that default. It's not your behaviour. It's that you do it without thinking. Once you start to talk to yourself and go, what am I thinking? You have switched off your autopilot. And then you have a choice. And sometimes you'll go, actually, you know, that the autopilot pattern or your way of thinking under pressure may well be what's required here.

And you've got choice, right?

Kate Christiansen (:But the problem is when you apply autopilot thinking to a brand new complex ambiguous situation because an autopilot cannot fly through that. You need to fly through that with your brain. And so in the book I talk about, you need to switch from autopilot to copilot where you are helping your brain.

That's a lovely use of language is not to manual, but it's to co-pilot. Yeah. I often say, does it have you or do you have it? And, you know, when you're on autopilot, it has you. You're in the hands of something else. You're not consciously choosing. You are just on doing that thing because autopilot is doing it. That it has you. But if you have it, you're like, that's me going, what am I thinking? yeah, I've got the driver going on.

And then you've got some choice. Would that serve this situation? What's the high purpose? And it leads us to a different set of questions, right? Which is, it's the discipline of being able to stand back from yourself. And you talk about these sort of three sort of versions of us. There's the cognitive thinking brain. Then you've got yourself who's able to stand back from that. And then there's your digital companion, which is AI. And I do love that.

being able to work with all three and recognizing that you have a role to play in that. You are the only one who can stand back. Your brain can't do it and the digital brain doesn't do it either. You are the only one who can say, is this right? Is this where I want to be? Because neither of the others, the brain works on instinct and the digital brain works on patents. So, you know, you've got to be the one in the middle.

And when you say you, it's interesting because most of us would go, yeah, I am my brain. But there's the way you refer to it. It's no, there's your brain. And then there's a different part of you that can stand back and go, hang on. Yeah, there's some different questions we need to ask. I'm curious, Kate, where do you find yourself falling into the answer trap for yourself? Where does that show up for you?

Kate Christiansen (:so often.

on podcast conversations where you ask early questions.

Yeah. I fall into the answer trap when things start to fall apart. The thing that my brain under pressure worries about and really gets concerned about is losing the plot. know, losing things, things not connecting up. And so anytime I feel things are fragmenting in lots of things, my family, here's a classic.

my family will give me a hard time because I'm the one that gets to the dinner table and say, so how was everybody's day? What were you doing here? And they're all like, nah, I just want to eat.

Stop being a connector.

Kate Christiansen (:Yeah. So even your thinking, see, that's my answer. My answer is I need to connect things up. What do I need to do? I need to connect things up. So it's not that your brain is focusing on the challenge or the situation in front of you. What it's focusing on is the problem that it thinks it has. And in my case, as someone who operates on a connector pattern a lot,

The problem is fragmentation. So what do I need to do? I need to fix the fragmentation and hold everything together at the expense of sometimes actually moving forward or at the expense of doing quality, making something more quality or at the expense of going and learning something. Cause actually maybe we need some more information.

What I'm doing is making a link between those five autopilot types and that's where you'll likely fall into a trap. I, know, I'd never really considered that being in a pioneer, which is the one that I tend to be most like, you know, like let's reframe it all the time, that that could be a liability. And I'm now starting to think that, actually, yeah, there is definitely times where we don't want to do that. We just need to get to some sort of good outcome.

and then try it and see what happens. And it's quite the epiphany for me, actually. It's like, ooh, all right. Because I can be a little bit evangelistic around the whole let's reframe things because I see we don't do it enough, but that's my problem I'm trying to solve. hmm.

We all do it. And this is when you know it and you see it in yourself, then you can name it and go, I think that's my connector. Maybe going a bit too far. don't need to be, know, resentful of it. It's the thing that makes you you. And it's the thing that it's the smart you like when you're firing with your pioneer thinking pattern, that's when you feel that your best, right? I'm on fire. I'm in flow.

Digby Scott (:addictive.

Yeah, it's absolutely addictive. then when you get in groups, I mean, I spend a lot of time working with teams and working with big large groups. And when they, when everyone else understands each other's autopilot and you can talk about that, it just, the friction just melts away, especially in the change space. You know, you're working so many, we're trying to work with transformation.

implementing AI, we've got all of these changes. Often what we see as being resistance to change is actually a collision of the autopilots. And I talk about the difference between alignment versus agreement. Alignment is when you think together, you cognitively align knowing that you and I have different ways of thinking and we cognitively align around what questions we're

answering because the answer is always related to a question and often, or most of the time we don't align on what that question actually is. we're answering the question that's in our head, not the question that probably needs to be answered. That's how you get off autopilot.

I think that's so powerful, you know, starting, for example, with what is the actual purpose of us coming together and trying to get some alignment around that question even is is really powerful. That's then the anchor for the rest of the work. Can I assume out a little? You know, this isn't just about decision making this whole thing. I think there's something much bigger at stake, which you've alluded to earlier on. But what do you reckons really at stake if we.

Digby Scott (:Don't address the perils of the answer trap as humanity.

It's one of those massive questions as to that you can answer it in a number of ways. So I'll, I'll pick one way and then do it. I think at the biggest level, this is about not just how we think, but how we define ourselves as human beings. The thing that we have used to make what makes us different is we've got a bigger brain than the other animals and, and we're smarter and this idea of intelligence and.

Okay, that's great.

Kate Christiansen (:Much of the thing that we used to put into say, intelligence is, know a lot and you have a lot of information and our education system has been built around that. now have something that knows a lot more than us can think a lot faster or give answers a lot more quickly. So if we don't recognise the answer trap and if we don't find a way to get out of it and

redefine what is our role, what is the role of thinking, what is intelligence, and we don't change, then what will happen is it will just erode what we have and then we'll be left going, well, what do we do? For me, some of the previewers that I spoke to who read the book and they said, you know, they've got young kids and they're saying, well, I can see this in my son already. What are the kids going to do if

We haven't said, intelligence, what is intelligence? So you go to university to learn stuff. Okay. So you don't need to learn physics. You don't need to learn science because all the answers are there. Where do they get their learning and experience if all they do is ask and get answers from a machine? It's foundational stuff.

I love the way you slow down again before you answer that question. I'm just noticing how you do this. So this is a bit of a meta moment that your answers seem to be really considered. You're not just like, right, here's what I know about that. And it feels like this is a sort of way of having a conversation that I think perhaps a lot of us could be developing the capacity to do. I just want to point that out because it's lovely.

because it gives me space to think about the answer while you're thinking about it. I don't know if you ever saw that before. I just wanted to say, hey, that's, I love what you do there.

Kate Christiansen (:Okay.

Kate Christiansen (:Thank you. Every skill that we have can be a double-edged sword, I think. And one of the things for me in my life and growing up and particularly in the workplace is working in a workplace where answers and fast answers and being very articulate and being able to rattle stuff off very confidently is recognised and being someone who doesn't do that.

It's taken me many, many years to actually recognise that the fact that I don't rattle things off, the fact that I do think as I talk and that can sometimes mean that I get to an end of a sentence and go, what was the question? I'm not quite sure. Where was I starting from?

Glad we recorded this.

So I think valuing, and I know a lot of people who particularly, know, change makers, system shapers, the transformation, anybody who's trying to get something to shift often sees the bigger picture and is often working with people who don't. And the ability to be able to slow down. And just as you said, when I slow down, you slow down.

in the conversation because we're in it and I can help to make that happen. And I think it's one of the really empowering things that talk about in the book is this, you might be in a culture where fast decisions are expected and where confident answers are expected and doubt is.

Kate Christiansen (:frowned upon and asking question is, oh look, don't slow us down. We need to stop navel gazing. But really, you are always the one who can change that moment. I deeply believe that in the way that you are and how you show up.

Yeah, it's always your choice, right? If everyone knew about the answer trap, you know, and that became language like, I don't know, like Carol Dweck's growth mindset, right? What if everyone was like, I completely get that. Yeah. How would that change the world? Do you think?

Hmm.

Kate Christiansen (:That would be awesome. I'll just go off on my own little land is what that would be. Look, if everyone knew the answer trap at an individual level, they would have so much richer thinking and so many more rich conversations. One of the problems with the answer trap is it's like a tightening spring because the more you make reactive decisions,

the messier things get, therefore the more complex things get more disrupted, then you make more reactive decisions and that sort of thing. So there would be a sense of relief. And I often talk about at the individual level, it's going from just feeling exhausted, which many, many people are to feeling energized because thinking when you're really on a roll and in flow is fun. So that's that.

level for the world and well for teams, just simply knowing the word and saying, think this might be an answer trap moment, changes the conversation and you do it in less than a second. And just imagine how much friction there is in organisations and teams because everyone's operating on their own autopilot.

trying to get their version of what they think the question is answered. And the world, like part of the reason for writing the answer trap is that there wasn't a word for this thing. We all talk, yeah, being a bit reactive. The ability to name this split second, this is not decision-making. This is thinking before the decision happens. And there was no word for that.

and just being able to talk about it. You cannot get out of it if you can't talk about it. And I think that was a real thing.

Digby Scott (:I think your gift to the world is the title of the book. You know, the answer trap says so much in three words and it's naming something as you've sensed. It's naming something that's been there all along that we've never really had language for. And by giving us that language, we're able to have a different form of conversation that unlocks something. That's the brilliance here. So to me, it's an incredibly

practical book with a really profound idea woven through it. So thank you for bringing this to the world and wrestling with it. You know, it wasn't AI that wrote it. It was Kate Christensen. It's brilliant. I always love to finish our conversations with this and, know, this is perfect for us, right? It's the curious question. What have you learned or been reminded of in our conversation?

think when you noticed your autopilot, the pioneer autopilot actually might not always serve you. What I learned from that is that when writing the book and immersing myself in this content, I was reminded of how easy it is to not allow yourself to actually go,

I mean, that's, that's a challenging thing for you, isn't it? go shivers, thing that I think makes me awesome. Maybe it doesn't always make me awesome all of the time. And I think that kind of that's typical you in terms of humility and curiosity about yourself. I think that was one of many sort of moments for me in terms of this conversation.

Brilliant. I'm glad that that's something that landed with you. If people want to get the book or find you, where can they go?

Kate Christiansen (:They can visit my website, www.katechristiansen.com.au.

And that's S-E-N on the end, isn't it?

Yes. Not S-O-N, S-E-N. There's resources. There's an answer trap risk profile. You can find what's my risk profile for the answer trap. So yeah, all of those things. And yes, let's get the answer trap, the language out there because it matters.

Absolutely. We're already doing it. Thank you so much, Kate. It's been brilliant.

Thanks, Digby. Absolutely awesome talking with you.

Digby Scott (:Just a quick reflection before we finish up. There's this story of these two young fish swimming along one day and an old fish comes by the other way and as the old fish swims by he says to the young fish, morning boys, how's the water today? And the fish swim on and one of the young fish turns to the other and says, what the hell is water? We don't see the thing we're swimming in.

And I reckon that's an analogy for the answer trap. I reckon in our culture, we're swimming in the answer trap. And what Kate's done is name something that exists that probably we haven't really examined before, this drive to answers, when in fact, we're better off slowing down, seeing our autopilots and learning how to ask different questions. There's so much in this. It's probably one of the most powerful books I've read for a while, and I'm gonna sit with it for a while.

Wondering what seeds have been planted for you, what you're wondering about, what you're reflecting on. And what you might do, and one thing you could do, is share the episode with someone else and get a conversation going about it. I this is important stuff. It's food for thought. If you want more food for thought, check out my weekly newsletter, which is also called Dig Deeper, which is full of practical, thought-provoking ideas around leadership, learning, and life. You can go to digbyscott.com.

and you'll get the very next one. I'm Digby Scott, this is Dig Deeper, and until next time, go well.