Episode 30

30. Letting Others Shape the Vision, Curiosity Over Certainty, and Why Leadership Isn't About You | Andrew Little

What if the most courageous leadership decision you ever make isn't about charging forward, but about stepping aside?

And what if the key to authentic influence isn't having all the answers, but mastering the paradox of deep confidence paired with genuine curiosity?

This episode explores the delicate balance between ego and humility that defines transformational leadership. We dive deep into how brutal self-honesty can become your greatest strength, why emotional intelligence is no longer optional for leaders, and how creating space for others to contribute might be the missing piece in your leadership approach.

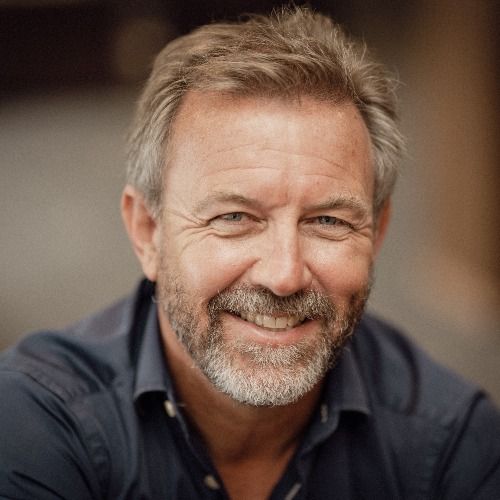

Andrew Little is a figure who redefined political courage in New Zealand by making one of the gutsiest calls in the country's political history: resigning as Labour Party leader just weeks before an election to make way for Jacinda Ardern. A former union leader turned politician, Andrew brings a unique perspective on leadership forged through decades of navigating complex stakeholder relationships, from representing workers to serving as a cabinet minister. His journey from a conservative household to progressive leadership offers profound insights into how our views can evolve while our core values remain steadfast.

You'll discover:

- How to balance confidence with "wonderance": the art of remaining curious while holding firm convictions

- Why reading your opponents' views strengthens rather than weakens your position

- How to create psychological safety where no viewpoint is considered "dumb" and everyone has access to leadership

- Why the phrase "you're either there to make decisions or make friends" misses the point of collaborative leadership

- How to process significant setbacks without letting them derail your purpose or self-worth

- Why showing appropriate emotion in leadership is a superpower rather than a weakness

- How to navigate opposing views by finding shared values and common ground

- Why the question "what is the why?" becomes your most powerful tool for building understanding

Timestamps:

(00:00) - The Paradox of Leadership

(11:18) - The Decision to Step Aside

(14:39) - Processing Emotions in Leadership

(20:44) - The Role of Collective Leadership

(26:00) - Navigating Opposing Views

(30:33) - The State of Leadership Today

Other references:

- 1981 Springbok Tour in New Zealand

- Andrew Little resignation as Labour Leader

- Engineering, Printing and Manufacturing Union

- Andrew Little to run for Wellington Mayoralty

You can find Andrew at:

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andrewlittle-nz/

Facebook:https://www.facebook.com/andrewlittlenz/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/andrewlittlenz

BlueSky: https://bsky.app/profile/andrewlittlenz.bsky.social

X : https://x.com/andrewlittle_nz

Check out my services and offerings https://www.digbyscott.com/

Subscribe to my newsletter https://www.digbyscott.com/subscribe

Follow me on LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/in/digbyscott/

Transcript

paradox of leadership is that it is a lot about yourself in terms of self-management and self-control, but it is totally not about you and it's about everything else in terms of what you do, how you conduct yourself and how you're communicating with the world. And it's keeping those things in the right places and in the right perspective.

Digby Scott (:One of the most important leadership decisions you ever made was to step aside. Well today I'm joined by Andrew Little, a man who made one of the gutsiest calls in New Zealand political history by resigning as Labour leader just weeks before an election to make way for his successor Jacinda Ardern.

I've long admired Andrew for that decision and I wanted to get to know the man behind the story. And he doesn't disappoint. Andrew opens up candidly and shares his personal views on how brutal honesty can be both a fatal flaw and your greatest leadership strength. He also talks about why leadership is paradoxically all about you and not about you at all and what it really takes to control your ego while still having the confidence to lead. This conversation, I reckon, will change how you think about making hard decisions and what it

means to put purpose before personal ambition. Hi, I'm Digby Scott, and this is Dig Deeper, a podcast where I have conversations with depth that will change the way you lead. Let's dive in.

Digby Scott (:Andrew, welcome to the show. It is, it's great. I've been wanting to talk to you for ages. I where we could start is a little bit about your upbringing. I found it fascinating to learn that your upbringing was in a right-wing family, but of course now you're known for more being on the labor side of the spectrum. Tell us a little bit about what that was like and perhaps if there was a realisation that, huh, this is interesting, how I've been brought up.

to bed.

Digby Scott (:Might be a different path that I'm heading.

My father was very political and very politically active on the conservative side of politics. He was a member of the local, the National Party, our conservative party. He watched a lot of current affairs on TV. As a young person, I watched that with him. So I got interested in politics through that. But he wasn't a conventional conservative supporter. He had some views that diverged from the traditional conservative platform. So he was very...

was wrong with his in the mid: I diverged politically was in:And what I realised is that my father was not very good at, he wasn't very good at arguing. He couldn't advocate his position. I found my system more compelling. And I think at the same time I was being exposed to other things. I was 16 at the time, so I was reading a lot more and there were just a different set of ideas that appealed to me. And I kind of just formed a view that my, although I respected my father and I didn't agree with his views. Growing up at home, he was very anti-union.

Andrew Little (:although he was, a teacher, he was in a very highly unionised part of the workforce. As I got through university, in fact, after university, my first big job was actually as a lawyer for a union. So, mean, something else happened along the way. I think what happened is I just became confident in my own views and exploring the way I wish to view the world and what I thought were important issues and went down that path and have been on it ever since.

Can I ask a little bit about what helped you become confident? Because I reflect on my own upbringing and my dad and I, yeah, we have very different views, still do. And I felt it was not a place for me to express myself because a bit like you, well, your dad, he didn't really argue, he just said what the truth was. And so I had to go and find my voice elsewhere. What were some of the catalysts or people that helped you find your voice?

s, that early:assertion of independence anyway, so he would go off and do things. the more I read and I guess at university I hooked up with people who I felt comfortable with and they were people who shared a set of views. The benefit of my upbringing was that I didn't find it difficult to engage with people with more conservative political views. And I felt quite comfortable having those discussions. As sometimes the case now, you see some people sort of take offense at somebody who expresses a diametrically opposite view.

I never felt the need to do that. I think my experience with my father taught me that you do have to argue your corner and be sure of your corner as well. I think what also gives me confidence, one thing I've carried with me, that some of my sort of good friends at university taught me this was never be afraid to read the opinions and so on of your opponent, of your political opponents. In fact, I think it's important to do that if only to test your own views. Not every conservative view is

Andrew Little (:is invalid or wrong. And there are some things, you know, I can quite happily agree with. There is some crossover, but I think you do need to test yourself periodically against the other ideas that are expressed. It helps you sharpen up your own views. And so I've always been more than happy to engage across the political spectrum. I haven't felt insecure about listening to and occasionally, you know, taking on board opposing leaders.

There's an interesting, almost a paradox, you said you've to be confident in your own views, yet you've got to be open to changing your mind, or at least being educated and broadening your perspective based on that, which I think is quite rare. What a gift you were given there because it feels like it's quite a rare thing in this day and age where it seems to be, we have to take a hard stance and that's it. How is that serving you beyond running for mayor or politics, but how does that serve you in life, being able to do that well?

think you're right about. think we're increasingly in an environment where there is so much available online and broadcast media. People can pick and choose or, know, kind of self-curate the news and the world as they wish it to be and get that reinforced. I think the habits that I had learned early on means that I still hold enough self-doubt to continue to be curious and to challenge myself. And

As I think I said before, ultimately that strengthens your view. It helps you develop a strong view. I think the other thing that helps me as a litigation lawyer, trained as a litigation lawyer, you what you often do, you seldom come across a case that is a complete slam dunk. There's always weaknesses and vulnerabilities to the case that you're mounting. And what you train yourself to do is to hone in on your strongest arguments and then kind of work out from there. But you always got to have...

the core argument that you retreat to when things get a bit tricky. And that just reinforces the strongest case that you've got. And sometimes the strongest case you've got isn't particularly strong, but you learn that tactic of going back to the last remaining kind of thing that you've got. And I think that's the same about your personal views as well. That thing about remaining curious, holding enough skepticism about what you're told, even by your friends and allies, just to be sure about.

Andrew Little (:the integrity of what you're being told or the cohesion of it or whatever it is. So in order to strongly express a view, you have to have those elements of ongoing curiosity, self doubt and self challenge.

And there's the paradox, right? Because I talk about confidence and wonderance, right? So this idea that you've got to have confidence, but you've got to have wonderance. And if you're too far, if they were on a spectrum, you're too far the other way, you're either arrogant or ignorant. And you've got to be able to just have that sweet spot. And you put it perfectly, right? And the benefit of that, I think, is something that we can all keep learning from. There's something about, you know, we all have ego, yet we can't have ego ruling us. That's what you're saying, I think.

I think that's very important, even as a discreet issue, think, and particularly in leadership. we know, look, in order to lead, and I, you know, if you think about leadership as very much a people thing, know, leadership only is meaningful when you're talking about your ability to work with a group of people and take them from a place to a better place. That's how I define leadership. And in order to do that, when you're engaging with people and when you're engaging with a lot of people,

Of course you have to have ego. You've got to have partly expressed confidence, but you have to have a sense of yourself and you have to have self-awareness and you need to understand the impact you're having on others. You need to have ego, but what you also need to do to be an effective leader in my view is to be able to control your ego. The irony or maybe the paradox of leadership is that it is a lot about yourself in terms of self-management and self-control, but it is totally not about you and it's about everything else.

terms of what you do, how you conduct yourself and how you're communicating with the world. And it's keeping those things in the right places and in the right perspective.

Digby Scott (:Absolutely. It leads me to perhaps what, you know, is a predictable place to go here, which is 2017 and your decision to step down as leader of the Labour Party. In terms of ego, to me on at least at a public demonstration, that was a demonstration that you were putting the interests of the party, interests of the people, well ahead of individual interests or ambition. What was going through your mind around that, that spoke to that tension?

The tension of me versus we, essentially, isn't it? What was that like for you at the time? I mean, it's a big question, right? Yeah.

Yeah. And I thought about it a lot since, and it's something that has defined me and who I am. I think it did reflect that who I am, which is that a number of things. First of all, in politics, I've never regarded anything in politics as guaranteed or that you can have any expectation about a particular kind of journey or achievement. Politics is totally about working with others and it's values based and it's about, you know, the end winning the confidence of enough people to be in government. So

we were faced with, I'd been in the role of what, two and a half years, the polls had set reasonably comfortably, but in an election year, we needed there to be a discernible lift. And actually, for a couple of months, polls, or in three months, but the polls were going the other way, to a point where I thought, I'm clearly not connecting or communicating effectively. that this is, I guess the other thing too about leadership is the one person you have to be brutally honest with is yourself. And that's about things.

self-aware and that's where you definitely have to shed your ego. But you've got to be honest and harsh with yourself and I think I am. So I had to think about what was best. I suppose to the extent there was a selfish aspect to it, it was that in the two and a half years I'd been leader of the party, I had lifted it out of a pretty dark space and a pretty poor space. And I've got the parliamentary party working well together. We've got good policy together.

Andrew Little (:everything was working well, all the systems and the people were all in place for us to do some really good things. But it got to that point at that stage before the election where the last remaining element, which was a leader who was connecting and then getting us that extra percentage of votes, I wasn't doing that. And I had to accept that. And it is difficult, of course it's difficult, because you're doing all this in the foreglere of the public. You've got to get under control of that.

It'd be easy to feel a sense of humiliation, probably unavoidable, and it'd be easy to beat yourself up. And that's the other thing in a leadership role you can't afford to do. Things go wrong, things don't go as planned, things don't work out. It's a question of then accepting the evidence, making a judgment call, and then going back to your basic values. What are you here for? Well, you're not here ultimately for yourself. In politics, you're here for your country, for your party, for the system to deliver.

And so that's what drove that decision. And my obligation wasn't at all difficult to discharge that, was once I made that decision, was to get him behind Jacinda, which I was very pleased to do and very proud to have done.

Absolutely. It also wasn't easy though, right? You know, from what I understand, you had a bit of a meltdown afterwards watching the X Factor and you know, the processing of that.

must have not just been a single point in time decision, right? know, change and transition are very different things. And what was the wake like for you, you know, the period afterwards? Because yes, you got behind Jacinda. Absolutely, I can understand that. And at some level, there must have been some hurting. There must have been some real processing going on.

Andrew Little (:Absolutely. And I think there's that, and I guess I see this in other aspects of my life too. There's the big decision. So you make the big decision. And then there's the anticipation of various things will happen and you kind of wait for that to hit you, the external things, the responses and all the rest of it. And you just got to brace yourself for that. The interesting thing about that was because it was so close to the election, the election campaign had kind of got underway. The media attention,

completely went off me, Rosandra Centre and everybody else. I took very much a back seat during the campaign itself. That opened up the more quiet moments, the more effective moments. And then the things that, the other things that unexpectedly triggered the emotional reaction. And that was, and I was clearly carrying those emotions, but I am someone who, look, I'm not impetuous, I'm not impulsive. I manage my emotions pretty carefully. My wife would do that.

But there are those moments where you do have to, you've just got to get hold of those emotions and let yourself go. And I had that opportunity a few weeks later triggered by, you know, I'm a sucker for the story of people who overcome adversity and disadvantage and do amazing things. I don't mean it's my story, but it's a story I'm always attracted to. And the people I have great admiration for and whether it's in politics or business or community, the personal

strength and insight it takes to overcome significant disadvantage and achieve great stuff. was always in my those people and then I was confronted with that story and and it just took me off. But it was good. It was a good release and it was a good time to reflect.

You've got to release, don't you? I had a friend years ago, she died in a car crash, and I got the news just as we were taking off on a camping trip. This was years and years ago. And I was so busy packing, and I got this phone call. We were like, oh, we've got to get on the road. We've got to get on road. And I like, I sort of buried the grief. And as we were camping, it was about a three hour drive south of Perth, as we were camping, this migraine came on. I never get migraines.

Digby Scott (:And it was there for three days and we had to, the pain was so bad we ended up having to drive me back to Perth and take me to ED. And they put me in a morphine drip, it was so bad. And I put that down to, gotta release, right? You've gotta have that outlet for processing hard stuff. And it sounds like it found its way to the surface like it did with me, also with you. How do you do that now? What's your outlet? What's your way of processing?

know, challenging stuff. How do you do that?

I've come to this much later in life than many others, but I now am more relaxed and easy about as emotions wash through me, is just to allow that to happen. I don't feel the need to control or manage. It's interesting emotions that way. Even as minister, I had a couple of situations where I, as I think is now more acceptable, you can talk about personal aspects of yourself, even in professional life and the public life.

And I found myself getting quite emotional about some things, talking about some family things. And I remember standing there, like on the two or three occasions, having to, you know, just go with it, you know, and express the emotion. It felt a lot better. I remember getting off the podium after each of those occasions, thinking actually, I think that was a healthier way to actually talk about the issue I was talking about. It was a quite personal issue. And I think we do have, and it's probably something that's happened in the last 10 or 15 years.

that in public life it is okay to clearly show emotional reactions to things. know, growing up in the 70s and 80s it was our community and political leaders showing emotion was seen as a weakness. Now I think it's seen as just something perfectly human and actually well defined somebody and I think that's a good healthy thing.

Digby Scott (:I think so too. And I think in this day and age, we're looking for humanity more than ever. And what we're lacking, think why there's a lot of cynicism around public leadership is because of the lack of that. And as humans, we need to feel that sense of connection and that sense of empathy. And you do it in your own way, right? And this, this...

I guess there's always this challenge of, how much do I share? What's appropriate? And what's just, as some people say, what's this therapy on stage? It's not to be able to do that. You seem to get the balance right. You're making that choice.

I have a view that public office has its own special set of characteristics. And again, you're not there for yourself and you've got to reflect a set of community interests or broader country interests or whatever it is. And I think people on average expect a level of gravitas and professionalism. But of course it's right at moments of great happiness. People look to public leaders to reflect that and moments of great tragedy and public grief.

People expect their public leaders to reflect that too, public office isn't his own kind of therapy session. It's gotta be, I think it's reflective of the circumstances and the moment. There will be times when the emotion you express is deeply personal and that's gonna be okay, but it is about judging the right thing. When it is right to do. We're all gonna have in our professional personal lives, a range of things.

that will generate a range of emotional responses. Not all of them need to be put on public display.

Digby Scott (:Absolutely, right. It's appropriate show of emotion. I want to rewind to a little bit to when you're talking about leading the Labour Party, you use the word I. So I took the party to a better place. think it's essentially I'm paraphrasing that. Yet, you know, it's not the act of one individual, too. It's a collective effort. What's your take on when you are maybe in the top chair, so to speak, regardless of what that is, what is the role that only that person can play?

versus the work of collective leadership.

It is about getting the right people in the right places. you know, think particularly in the political realm, but I suspect it's the same in anywhere. People want to feel a sense of purpose, a sense of positive purpose, doesn't matter what role they're playing, who they are. If you're engaged in a group, then people want to feel they've got a role and it's purposeful. And so the leader's role is to make sure that people do feel a sense of positive purpose. People want to feel as if they have an input.

that their input is valued. So it is the leader's role to do that. I think it is the leader's role to make sure, know, particularly in that political environment where it is easy for some people to think they're being left out or being treated differently or worse, is to make sure that everybody understands that everybody's getting a fair chance and that people are being used to the best extent of their skills.

The leader's role is to reinforce some basic values every now and again. And that's what you do. I think what I was able to bring, why I can individualise it, is that sense that hadn't been in place before, that everybody had access to me. There was no such thing as a dumb point of view. And if people were concerned about something, the right thing was to express that concern that people shouldn't bottle it up and keep it back. So part of it was as leaders,

Andrew Little (:Getting the cultural settings, you like, right. Your organisational cultural settings. So that people could function with confidence and with a sense of purpose. That's the role of the leader. But in the end, what does that lead to? A well-functioning team. That's what had to be delivered. That's the we part of it. That's the outcome.

Tell us about a time when that approach was tested for you or, you know, it's kind of like when you're in the cauldron in the fire where perhaps that, you know, either you came out of that going, I'm going to lead in a different way because I didn't get it right. Or you saw someone else do it and you went, okay, that's how you do it. Tell us about a time that, you know, was one of those epiphany moments where you went, okay, I've got to put that into my playbook now.

Actually, was a previous, when I was union secretary of what was then the engineering printing and manufacturing union at the time, the largest private sector union in New Zealand. And I came in at a time when it had a very good longstanding leader and he had stepped aside, but the structure needed reinvigoration and changing. And there were some big challenges that had to be addressed. And so I lead a change process and it was very challenging. It demanded a lot.

of time and energy and insights. And that was probably too early in my time really for me to bring a lot to bear on it. I was very fortunate to have some much more experienced people around me who I hadn't involved in the process to begin with and realised probably later than I should have done that actually they had a lot to contribute. That's where I learnt that thing about never assume that you know it all or never assume that your great vision, everybody's just going to hop on board.

because a lot of people would have different versions of a similar vision and there'll be some lot of things you can add to it as well. So the restructuring process I was doing was getting ground down. In fact, I was worried that it might just stop completely. In fact, the easy way out would have just been to say, you know what, this is too hard. I mean, the other lesson I learned, I'd learned previously was in leadership roles, the mantra I'd kind of learned in a previous.

Andrew Little (:leadership role was, look, in leadership, you're either there to make decisions or make friends. And if you're there to make friends, all well and good, but don't expect to make a lot of progress. That helped me when I realised that the approach I was taking needed some help and the help of others. That wasn't so much the making friends thing. It was in order to get good decisions made and a vision realised, be prepared to include others. What that leads to ultimately was

We got through a of decisions, made a big restructuring and the year after it was all completed, we did face a major challenge and the organisation wide response was just incredible. And we actually did things that the organisation could never have done before and it kind of vindicated what had happened. What it also vindicated was the value of being open to letting others help you shape and give them a stake in it because the other one's going to

help you make it work when the next challenge comes along. And that's what happened.

There's something about again, letting the ego step aside here, isn't there? You know, it's for a vision that's a collective idea, not just your idea. Given that, you know, there's a lot of division around the moment for future leadership roles for you, whether it be mayor, whether it be something else down the track. What's your playbook? What's your approach when you've got opposing views, you've got people saying, no, you're wrong. I'm right. Whatever it is. How do you be in the middle of that in a way that

unites or at least gets opposing views to listen to each other. How do you do that?

Andrew Little (:First, you've got to hear people out, you've got to listen to what they have to say. And then I think it's about the dialogue and the discussion about finding the common ground. And it usually starts with some shared values or shared principles. And then a discussion about how do we realise those with what we've got in front of us. And then working on, do we agree that we're under some constraints, there's a limited number of things we can do or limited number of approaches? Or if we disagree with that, tell us what...

the range of other approaches are. I think that works a lot. There's always going to be difficult personalities around, but I think they are fewer than people think if you just take the time to work with and listen and talk with people who you might otherwise disagree with. I go back to kind of what I learned pretty early on, which again, probably reflects my upbringing is that I don't mind if people disagree with me. In fact, if anything.

If people instantly agree with me, I'm usually immediately suspicious. Oh, well, what do you want? know? Because I'd only said that my views are insights and is a perfect, that can always be modified and improved and shaped and all the rest of it. So I'm certainly open to that. But there's no substitute for that dialogue and discussion. And I think probably in this day and age, you have to say it. It has to be respectful and courteous. There's no room for the stridentcy and the profanity that often goes with

views, especially those expressed online, because views expressed online tend to be, you know, views expressed with a screen and a keyboard, not with another human being sitting in front of you. If we can get back to those time-honoured sort of things of dealing with each other and finding the ability to talk with each other, regardless of disagreements, it's amazing actually what we can come up with. You know, we can synthesise something that's pretty powerful.

I agree. think a friend of mine says, give him a damn good listening to. And because there's this deep human need to be heard, to be seen. And if we can give the gift of that, then we're opening a doorway to, what do we have in common? I think that's exactly right. So yes, I am agreeing with you in that. I think we've lost the art of explaining how we came to our perspective. And it's interesting coming way back to your dad, right, and how he couldn't.

Digby Scott (:argue his point. And I'm wondering whether he had the skill, did he not have developed the skill to be able to go, and here's my logic, here's my process, here's how I've come to that. I don't see that very often, this here's my rationale, because maybe we haven't really thought it through. And there's an accountability I think we need with that. How do you bring that out in people?

I think that is important. think the question often is asked is what is the why? And that's, think, if you maintain that level of curiosity and large extent introspection and sometimes introspection is sort of frowned upon. Actually, you still need it. You still need to be able to challenge yourself and query yourself. I do that. I like to know that I can explain or justify what I'm doing and I like to be able to do it on the grounds of principles and values.

And obviously the evidence. think one of the things that we also see in debates on social media is what people consider to be evidence sometimes isn't particularly reliable evidence. Some people confuse assertions with reasoned evidence when it's not. We're going to have to work through that. It does, I think, then underscore the need for those in leadership roles to be able to demonstrate.

those skills of explaining why, providing the rationale. That's ultimately what will help to give people who you want their agreement to give them their why as well. That's what you want. And that's respecting people's own intellectual capacity to think, form their own judgments and make up their own minds. But when you're in a collective endeavour and you need as many people as possible to reach sufficient agreement and sufficient sharing,

We've got to help people find that path to what is the best answer right now for the problem that we've got.

Digby Scott (:Yeah, absolutely. When you look around and ahead and you think about the state of leadership, maybe in New Zealand, maybe globally, what worries you the most?

Certainly in public office, there is this sort celebritisation of leadership. And look, of course there's going to be, you know, the more kind of senior and important the roles, there is always going to be an element of celebrity. The way leaders, public leaders now need to communicate and reach an audience, you can't avoid that aspect of it. But I think it's the element of playing to the camera, a number of leadership roles.

And in fact, in most organisations, even private organisations, there's that aspect of the leadership role, which we describe as the bully pulpit. Probably not the best term these days, but it's the opportunity that goes with a leadership role to persuade and communicate that no other position or role in the organisation has. And so it ought to be a valued and treasured opportunity, but one exercise very carefully in my view. And I just think we've turned the...

bully pulpit element of a lot of public roles into something that is not about persuasion or uplifting or enlightenment. It's become something a little more negative. But that said, look, it is becoming a lot more challenging because of the level to which a range of diverse views, including some quite marginal and extreme views, are now given a platform and shapes the public discourse.

you know, the challenge of leaders is to navigate that and keep focused on something that is as positive as possible and positive in the sense of it charts a way forward or explains a decision about change or even explains a decision about why something isn't going to change, you know? Yeah. But it's about finding the way to do that that doesn't get drawn into or distracted into these more kind of marginal ends of the public discourse.

Digby Scott (:Absolutely. So I ask you what worries you. I want to ask you what's giving you hope.

I guess I worry about the easy access to information. use that term as broad as thing. Access to information, however accurate or inaccurate it might be. There's just an avalanche of it all the time. And learning the discriminating tools to sort of gauge what is more likely to be credible and what isn't, I think, is getting harder. That concerns me. I think, however, whether it's related to this or not,

we still see in the political realm, you know, it's really good progressive causes being well articulated, activating people and keeping those important, and for me at least, those moral messages about humanity at the forefront.

What's an example of that that you're seeing at the moment?

ael of the attack in October,: Andrew Little (:There's a consciousness about that and some organisations doing amazing things. Cities and communities work because enough people care about each other to keep it together. Ultimately, that's what makes us human is our ability to empathise with others. And as long as we've got organisations and people doing that, then I remain hopeful for the future of humanity and improving life.

You've got to be, don't you? Yeah, and it seems to be a lot of grassroots stuff that you see is that's what I'm seeing a lot of is like, this is where the hope lives right now. What's your growth edge at the moment? What I mean by that is like, where are you learning right now? Like, what's the stuff for you as a leader, as a human, where you're kind of going, here's my next lesson.

lot of that at the moment. So as a candidate for the Wellington Merit, I'm meeting a lot of people and actually a lot of people referring me to various books and sources of information and analysis and insight. And like even in the last two or three days, I've been to do a number of seminars and sessions and just educative discussions. I can tell you last night, I didn't sleep particularly well because I've just got so much going on in my mind about

Yes, I hadn't thought about that before. I hadn't thought about that. And here's a resource I can go to. I'm looking forward to sort of checking that out. So I'm feeling in a pretty excited frame of mind at the moment. know, clearly I've got a campaign. I've got to get elected. But I feel like there's a lot of people around me who are giving me some really good stares. There's a whole world of knowledge opening up to me that I wouldn't have been exposed to had I not been on this journey.

That's brilliant. And again, there's that openness to new right there in the way you say that, which I think, yeah, it's the, huh, all of this stuff. And obviously there's, you've got to have a way of processing that some stuff you'll forget other stuff you'll take further. But the fact that you're open to it, this is awesome. I was finished with a question that you couldn't have known before we started this. You couldn't have known the answer before we started our conversation. The question is, what have you learned or been reminded of during our conversation?

Andrew Little (:The questions you've asked have taken me right back. But I think the main thing I would go back to is that sense of curiosity and still being able to challenge what you're seeing in front of you, keeping an open mind. And that doesn't mean to say you never latch onto a firm set of values or principles or even views. I think I have a very clear set of views, but I think it's important to remain curious, continue to challenge yourself.

because that's what in the end makes you stronger personally. That's what equips you to be, if not a good leader, a reasonable one.

let's go with good. Come on. Absolutely. No, it's been brilliant. And you've demonstrated that all the way through this conversation, Andrew, the curiosity, the openness that there's one leader I know calls it looking for the disconfirming data. You know, it's like, what else could I be learning here? Right. And, know, you've got that in spades. We should the best of luck. You're not going to need luck, I think is the best of intent, the best of the journey ahead for the Merrill race. But also whatever comes.

in whatever direction you go, because you are a wonderful contributor to society and I admire how you show up in your leadership in the way that you think. I really appreciate you making the time.

thank you

Digby Scott (:and we'll see you soon.

Digby Scott (:quick reflection before we finish up. After that conversation with Andrew, I've noticed a theme, not just with Andrew and what he was saying, but with a lot of my guests and a lot of high quality leaders that I come across, which is maintaining that curiosity, maintaining that balance between confidence, knowing what you know and owning what you know.

but knowing that you don't know it all and having the wonderance to be able to go and what else and what if I'm wrong and what can I learn from this person in front of me? And I think there's something about the skill of being able to do that can set us apart in our leadership, in our ways to not just influence others but get stuff done that matters because in Andrew's story you hear that, particularly his union story, his lesson of

learning to invite others in, particularly the ones who might have a different view. And there's something about putting the ego aside, bringing humility to the fore and be able to go, you know what, hmm, maybe there's a different way and maybe I don't have all the answers. And what if we could all do that? What if we could all just ask those sorts of questions a little more often? What would happen? Curious about what this has got you wondering this episode?

you took from the conversation with Andrew Little that you might put into your playbook. If there's something that has inspired you, got you thinking, got you wondering, please share that and this episode with someone else. Get a conversation going. Also follow this in your favorite podcast app because there's a bunch more to come and there's a bunch more in the back catalog as well. You might also like what I write, which is also in the newsletter called Dig Deeper and you can get that at digbyscott.com/subscribe.

I'm Digby Scott, this is Dig Deeper, until next time, go well.